Ethnography Issue ❸ ↓ Interview

Brought together through their connections to Tibet, Carole and Rima met in person for the first time to discuss female strength and Buddhism, the ethnographic power of art, and Rima’s exhibition “Empowering the Extraordinary Dakinis” which ran earlier this summer at Tibet House in New York City.

Carole McGranahan — Rima, I want to start by reading the short text that introduces your exhibition. It reads: “This exhibit presents artist Rima Fujita’s recent works exploring women’s spiritual roles through iconography, tales and figures from the Buddhist tradition and other spiritual cultures, as well as modern influences.” Can you tell me more about the impulse and the spirit behind this art?

Rima Fujita — For years, I’ve painted women and people often ask me, “Why don’t you paint men?” It’s a good question. I paint my dreams. In other words I paint the visions I see in my dreams, the dreams I have when I’m sleeping or in meditation. Women always appear in my dream and men hardly come visit me.

CM — And thus, they aren’t as present in the art.

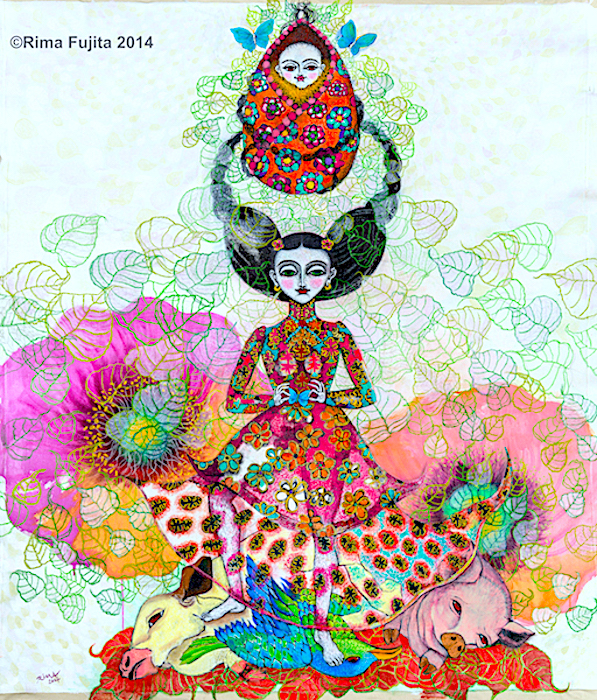

RF — Right. I’ve always painted women. Over the last several years, I started thinking that I wanted to do something to do with female power. Last year the exile Central Tibetan Administration in Dharamsala, India asked me to help them create their first sexual health book. It is called Rewa which means hope in Tibetan. They refer to it as a sex-ed book, but the content is actually about girls’ empowerment. Working on that project really finalized my desire to do a series about empowering women or female power. At the same time, I was thinking about Buddhism. People often tell me that I am a dakini, and I’m like “Oh, am I?” in a very skeptical sense. I started to read and study about dakinis and deepened my understanding of them as active, wrathful female spiritual guides or muses. I began to practice chöd, which is a meditation method linked to dakinis; it’s called cutting through the ego. That’s how I came up with this exhibition theme.

CM — Women’s participation and power is such a prominent theme in Buddhism right now, too, and especially in Tibetan Buddhism—the possibilities for women with debates over whether nuns can be fully ordained or sit for a “geshema” degree, the equivalent of a PhD, both of which have historically been limited to men.

RF — Yes, there is gender discrimination in Buddhism and yet there are so many powerful goddesses. Why is there this discrepancy? All of these thoughts and experiences came together in this exhibition.

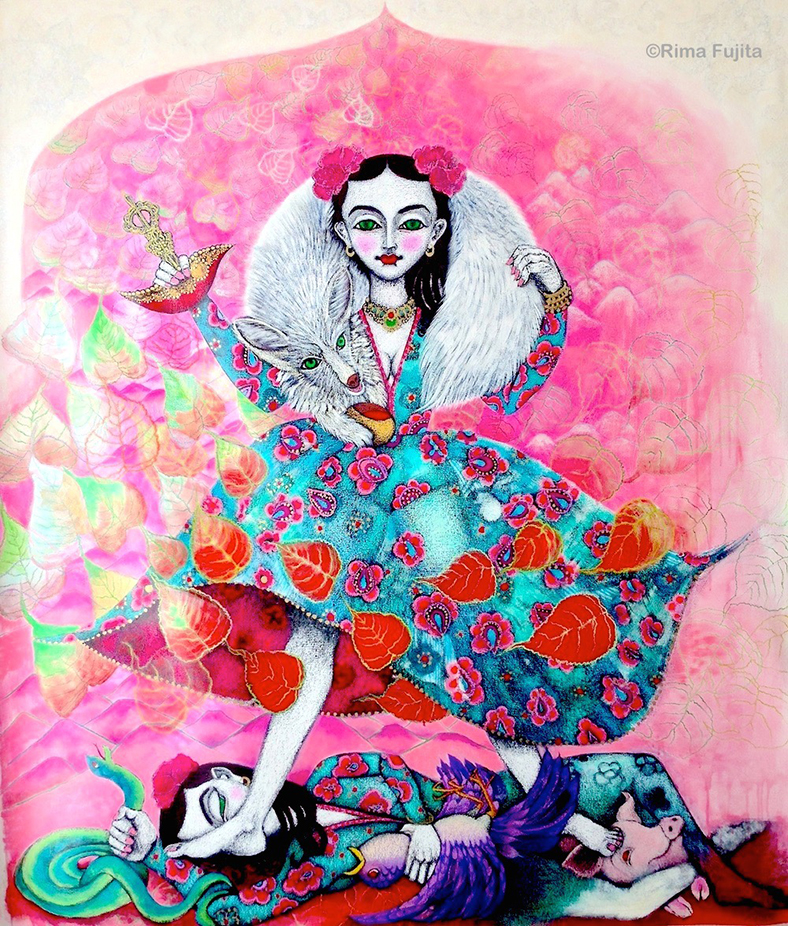

CM — The exhibition centers on six new paintings of yours, two linked trilogies that present different images and ideas about dakinis. Let’s talk about the first painting in the first trilogy, the one called “Chöd.”

“I realized art was only a tool. You have to use the tool to serve the society or help others or do something.”

— Rima Fujita

RF — I saw this exact vision in my dream before I painted this. Sometimes people ask about why I have painted this or that, and a lot of times I have to say, “I don’t know.” I am painting an image I saw in my dream. What I like the most in this painting is the silver fox around her neck. It looks like a fur coat, like fox fur, but actually the fox is alive and is holding a skull filled with blood, which is a symbol of dakinis. I’m an animal rights activist so it was really nice to see the fox alive in my dream. In Japan, where I was born, dakinis always travel with silver foxes. I’ve never seen that in Tibetan Buddhism or in any other Buddhist tradition. I think it shows my background or heritage. I think that the woman standing in this painting is killing the woman on the ground, who is not a separate person but is herself. She is killing her own ego to have a beautiful transformation and a new rebirth.

CM — This is something that’s so striking in Tibetan Buddhist art, some of it looks really violent for people who aren’t trained in how to read it. The wrathful deities and fearsome ones are actually doing a lot of work to help people grapple with different emotional problems or the different vices, including ones of character and ego that we all struggle with. It’s so evident in all of these images.

I also find this painting, and all in these two trilogies, to be unique, beautiful examples of the Buddhist interconnectedness of things as well as intercultural connections between Japan, the USA where you have lived for over thirty years, and Tibet. Here we see dakini practice across these different strands and locations of Buddhism.

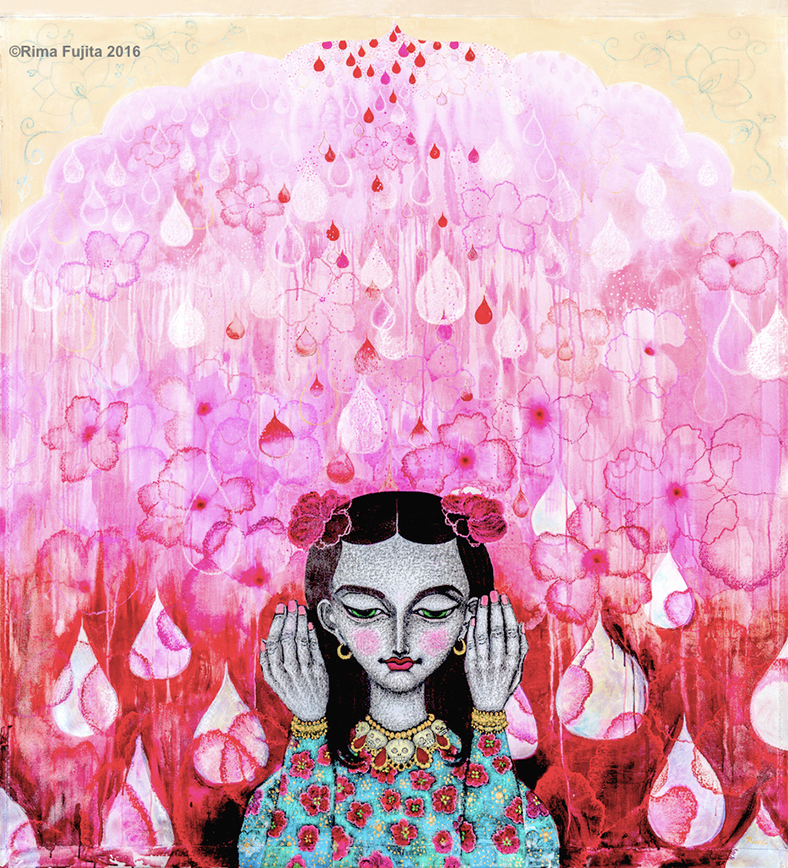

RF — Yes, with exploring women’s power at the center of all of them. The second painting is called “Bliss,” and it looks like teardrops or raindrops perhaps coming down. The woman looks so serene and at peace, almost as if she is trying to receive this blessing from the heaven. To me, the rain looks like blood, and blood symbolizes women or life, because as a woman we deal with blood once a month. It’s part of our body. It’s part of our life, without blood we’re not alive. It really symbolizes female power. To me, it looks like this woman is so blessed with this rain of blood or shower of blood and visually it’s beautiful. It’s not grotesque. It’s actually one of my favorite pieces.

CM — In many cultures blood is something that is categorized as either very pure or very impure. It has power in its polluting aspects, and thus a woman’s menstrual blood can be incredibly potent.

RF — I remember once, I was in Bali visiting all these beautiful Hindu temples, and at one temple the guard at the entrance door said, “You have to wrap with this.” He gave me a wrap to cover my legs, which was fine with me, but then he said, “If you’re having a period right now, you can’t go in.” I remember I was so upset. I thought, “How could you? How could you say such a thing?” but since I was a tourist I didn’t want to fight with a local tradition. So I did not say anything, but that made me think a lot about the whole issue. This was a long time ago, but what’s wrong with our periods? Why do you see it as a dirty thing? Why is it disgraceful? All those questions stayed with me for many years.

CM — One of the things that I see so powerfully in this exhibition is the Tibetan tantric religious practice of inversion so that menstrual blood is no longer polluting, but is instead seen as life affirming and life giving. It’s a source of power, so you’ll see deities standing in a pool of menstrual blood; here is the dakini world. I feel that your art is trying to open that conversation for folks not necessarily versed in Tibetan tantra, to invite people in to thinking about gender and bodies and power.

RF — I hope so.

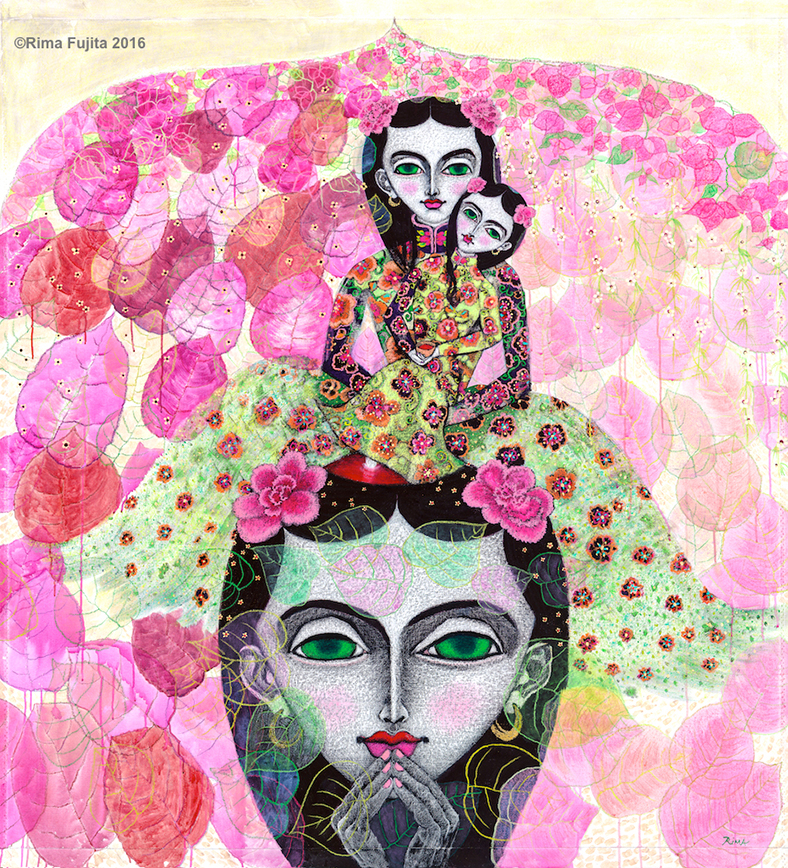

CM — I hope so too. The third painting in this trilogy is called “Cutting Through the Ego.”

RF — My book projects are that for me too. Rewa and the others I’ve done about the environment, tuberculosis, folktales—they all combine art and stories in Tibetan, English, and Japanese. I make them for Tibetan refugee kids and have donated over 12,000 books to the community. Until I started making the books, I didn’t know the purpose of art. Eventually I realized art was only a tool. It was not the goal. You’re an artist, you have a talent, you have to use the tool to serve the society or help others or do something. Use your talent to be of service.

RF — This image is literally of the cutting through the ego meditation method. It shows the step-by-step method by which you visualize yourself, and then you chop up yourself physically, and then you put yourself back together. You imagine yourself as a small child and you put yourself back together as a small child into your brain.

CM — It’s a practice with a specific series of progressions and moves you make.

RF — Which when you explain it sounds horrible.

CM — And violent.

RF — Some people say that it’s very dangerous as well, but when I first did chöd meditation I loved it because, as an artist, I battle with my ego every day. It’s a constant battle and this meditation really helps me to reduce it. When I say ego, I mean a bad ego: negativity, fear, ignorance, attachment, all those negative forces. I don’t eliminate them entirely, but I can reduce them for the moment.

CM — I am struck by the woman in these paintings. It is the same woman across the six paintings (and in other works of yours too), and the same woman appearing multiple times in the individual paintings. In “Cutting Through the Ego,” she appears multiple times in full body, as just her head, as standing on another version of herself, and so on. There is a real sense of transformation, of purposeful transformation. And this sort of transformation is built into your artwork as well, into your style.

RF — Working on a black surface is my signature style. My work started to be known for that particular style when I was in art school in New York. All I did was line drawings. Over and over I was doing all line drawings so I became really good at it. Whenever I drew or painted, my lines were perfect. It looked great, but to me when art is perfect it’s boring. I know most people strive for perfection, but coming from Japan, we have an aesthetics called wabi-sabi and what it means is you have to find beauty in imperfection because nothing is perfect in this world. Rather than striving for perfection, you appreciate something in front of you and you find beauty in it, or you give it meaning yourself. It’s a deep aesthetics that I respect all the time. I wanted to avoid drawing lines so I came up with this idea to paint the surface of the canvas. I paint the white surface black, and then I lay the colors and leave spaces which become black lines. This way I don’t have to draw lines and it creates a kind of quirky, uneven, unbalanced, but beautiful space of lines. That became my signature style. I’ve been doing this method for 25 years now.

CM — So the work has imperfections built in to it. Your art is constituted in that space of imperfection. In some ways, anything that claims to be perfect, for me as an anthropologist that would be where I would stop and say, what is going on? Any time there are claims to some sort of perfect truth is where you pause and ask questions. Culture is a system of lived contradiction. We all have cultural frameworks for both making and making sense of the world, and these are both imperfect and impermanent too in a sense. I see your art as traversing several worlds and pulling in all of those contradictions and trying to think about them. The thing about that is it is not debilitating. You’re not paralyzed in forging ahead despite the contradictions involved. That is, in some ways the condition of life is accepting the imperfections. The imperfections don’t actually stop us. They’re part of our movement.

RF — That is interesting. I never thought of it that way. I love it when other people can interpret my art.

I believe there are things which exist that we don’t see. Black represents that world. My work is with the light on the black surface that lights these things so that we can see them. Rather than constructing, my work on the black surface is almost like a deconstructive method. I believe those images exist already because they come to me through my dreams. My job is to put the lighting on them so they can be seen.

CM — I love how you call that deconstructive. I wasn’t expecting an artist to talk about creating something as actually being deconstructive—but you’re right. You’re illuminating and bringing to life what’s already there.

RF — My work is always deconstructive because I’m not creating something which doesn’t exist already. They exist somewhere. Those visions, I don’t create them. They come to me from somewhere. My job is to execute the paintings in those dreams.

CM — In some ways, that is similar to what an anthropologist does in finding the stories that are already in the world and that haven’t yet been told. Telling these stories, making this art, and then sending both out into the world and thinking about the work they do. Art can’t be only about the artist and scholarly work is never only about the scholar. Instead, there is a responsibility to think about what an essay or a book or a painting is going to do in the world once it is completed. This is the idea of the scholar and the artist being of service in some way.

CM — As an anthropologist, I find myself turning more and more to art, especially to contemporary Tibetan art to understand the stories people are telling me or a particular historical moment or, say, Tibetans’ relationships to someone like Mao Zedong. Sometimes art is what I need to understand a particular cultural or historical or political moment. Art can provide ethnographic context not always found in the spoken or written word.

RF — Art is so particular and personal. I really don’t expect to like or even understand my own art, and whatever viewers feel or interpret is up to them. I’m not the type to say, “Oh, this means this.” You can look at the same painting every day and see and feel it differently. You find something new each day.

CM — Even when it’s your own painting?

RF — Sometimes I think, “Did I paint this?” I even said this at the opening for “Empowering the Extraordinary Dakinis.” To me art is something you communicate with the heart. The art of today has become too cerebral. It’s all about our brain, our intellect, you have to understand this and that and that. To me, if you hate it, that’s fine. Art is meant to talk to your heart or stir up some kind of emotion or memory from the past life, some karmic connection. To do so through here [touches her heart], not through here [touches head].

CM — Through your heart, not your mind.

RF — Yes. Some people don’t communicate with art that way and that’s okay, because my art is not for these kinds of people. It’s okay. It’s a lot to take on. To me, my art is a success if I can make any kind of emotional connection with the viewer.

CM — I think we can call this exhibit a success.

RF — Thank you. ●

—

Rima Fujita was born in Tokyo, lived in New York City for thirty-two years, and now divides her time in NYC, Southern California and Tokyo. She graduated from Parsons School of Design, and has exhibited her work internationally to much acclaim. As a founder of her organization, Books For Children she has created six books and has donated 12,000 books to the Tibetan refugee children in exile. As a descendant of the Last Samurai her creative aesthetics is strongly influenced by the philosophy of Bushido and Buddhism.

Carole McGranahan is Associate Professor of Anthropology at the University of Colorado. She is author of Arrested Histories: Tibet, the CIA, and Memories of a Forgotten War (Duke University Press, 2010), co-editor with Ann Laura Stoler and Peter Perdue of Imperial Formations (SAR Press, 2007), and co-director with Losang Gyatso of the Mechak Center for Contemporary Tibetan Art. Currently, she is researching and writing about refugee citizenship in the Tibetan diaspora in Delhi, Kathmandu, New York City, and Toronto.