What to do with the Present

The year is 1998. Luka [names have been changed] is four years old. He receives a gift so big that he is unable to hold it in his hands. The gift is wrapped in colourful paper with a bright blue ribbon. The boy is excited. His mother helps him open the present. Luka’s eyes open wide as they gaze on the shining object in front of him. It is the largest gift he has received that day. He can’t wait for his mother to open the box. But Luka’s mother takes the present away. He will never see it again.

“What on Earth will we do with this present?” thinks the boy’s mother, Tania, to herself. Part of her wants to yell, “Seriously, what were you thinking?” The box boasts that it contains a “realistic rifle and gun”, with “a couple of grenades,” all with “lights and firing sounds.” Tania’s thoughts follow in rapid succession. “It is just a toy.” “Poklonu se u zube ne gleda! [don’t look a gift horse in the mouth!]” Furthermore, the present has been given to her son by a newly acquainted family who came to Australia as refugees from a war raging in their common country of origin. They have gone through some trouble to pick up the present, knowing that money is extremely tight. But, as she looks at the gift, Tania is reminded of her nightmares. In those nightmares, armed men would visit and threaten her family. And in the box are replica artefacts of what these men would carry. “Listen, they are really nice people,” she tells herself. “Whatever the reason for choosing this present, I am sure they mean well.” And so, Tania smothers her gut reaction and replaces it with the socially acceptable convention of thanking the giver.

Children, of course, love toys. Parents usually love them too. Toys remind them of their own childhood, when life felt simpler and at times even magical. Children use toys for play while adults use them for multiple purposes. Adults give children toys to entertain them and gain free time for themselves. They also give children toys with the intention to educate, to further facilitate development of children’s bodies and minds.

Toys also represent the transfer of values, of cultural heritage and hopes for the future, for both the child and the community. In this sense, toys are usually about much more than what they seem[1]. They unveil ways in which adults communicate their expectations about children’s future role in society and teach them implicit values about their culture and identity. Like all cultural artefacts, a toy has symbolic meaning, and can tell us a great deal about the larger society in which it is situated[2].

In the past, toys were scarce and confined to the wealthy. Industrialisation, the invention of cheap materials such as plastic, and the consumerism of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries impacted the production of toys. The making of toys has now become a major global industry. The current revenue from toys ($90 billion) and video games ($130 billion) is projected to exponentially increase into the future.

As toys and games have proliferated, so has the volume and complexity of research into their impact and significance, including analysis of industries’ marketing strategies. There exists decades of research into the roles some toys and games may have in condoning violence and aggression, as well as research into gender-typing of toys. A majority of studies conclude that, by and large, girls are given toys which focus on a future role of mothering and taking care of the household (i.e., Baby Born and kitchen play sets), whilst boys are more commonly given toys which centre on sport, action, or adventure (i.e., treasure hunt games and sport equipment). Professor Judith Blakemore has further investigated gender-typed toys on a continuum, arguing that toys expressing and encouraging “strongly masculine” roles focus on violence, fighting and aggression while “strongly feminine” ones focus on attractiveness and appearance. Perhaps surprisingly, research by Dr. Elizabeth Sweet has shown that toys and their advertisements nowadays are more divided by gender than they were 50 years ago.

There is also a consensus amongst researchers considering the choices boys and girls are offered. Given the overall higher valuing of male traits within most contemporary societies, girls are encouraged to embrace what are considered traditionally masculine qualities, including strongly masculine ones. The choices for boys, on the other hand, are more limited. For example, in a number of recent Disney movies, the girls have embraced the sword, but very few boys turn up looking like princesses. Researchers in the field of critical men’s studies point out that one of the worst insults for boys is still “sissy,” or similar words that question a boy’s masculinity.

This is a chicken-and-egg type of situation: culture influences the development and production of toys and games, which then in turn influence cultural values, personal and group identities, and the imagination of one’s own place in the community.

If there is expert consensus as to the gendering of toys, there is less agreement about the roles played by nature and nurture, possibly due to the difficulty in neatly distinguishing the two. Evolutionary psychologists argue that it’s impossible to socially engineer how children play, and that even one-year-olds prefer gender-typed toys. Many parents argue that boys given dolls will dismember them rather than engage in gentle parenting; they will turn sticks into guns, so not giving them toy guns is “pointless.” Peace researchers, however, argue that this phenomenon is not universal: they have found little evidence of such behaviour in historical and contemporary peace-oriented societies and communities. Furthermore, some peace, gender, and psychology researchers also point out that adults in many contemporary Western societies give boys messages that promote aggression in subtle ways. For example, boys are told to be caring and kind but also to be tough and “man up.” They are to share but also to strive for the top. Despite physiologically being able to cry, they are most commonly told not to. Instead, they are taught from an early age how to channel their vulnerability and fear into anger, rage and revenge.

But does such gendered play and psychology translate into real-world violence? Moreover, do violent toys or games (such as the first-person shooter genre) drive some young men to commit murders, as the media often suggests in the aftermath of mass shootings? Responses are complex, but they can be grouped into two basic and opposing camps. On one hand are studies supporting the argument that boys who play with military and war-themed toys know the difference between play and real aggression, and that those toys usually fit in with styles of play that already exist. Researchers in this camp argue that at worst, such toys and games promote aggression and violence during and immediately after violent-themed play, but not in the long term. Other cultural factors may and do override what children take away from play.

The other camp points at the overarching cultures of violence within which such toys and games exist. Peace and gender researchers point out that over 90% of all recorded acts of direct physical violence in the world are committed by men. Men continue to be “violence subjects” as well as “violence objects”[3]—disproportionately injured and killed through violence. There is a belief in many contemporary societies that it is somehow less bad to kill a man than a woman, and that a task of aggressive killing is a “man’s job.” Men are therefore expected to turn themselves and other men into violence subjects/objects during wars or while competing for resources and power in general. In strongly patriarchal warrior societies (i.e., those preparing for and waging wars), the predominant view is that every man is, by definition, a (potential) soldier. At an extreme end, this underlying view explains the genocidal practice of killing unarmed teenage boys as a “preventive” strategy during violent conflicts. At the less extreme end, it explains ways in which some tools we create — inclusive of toys and other cultural artefacts — shape us, and vice versa. Peace researchers therefore ask us to take a broader and longer view and ask the following questions: If we were to dedicate ourselves to changing cultures of violence into cultures of peace, would we even create play artefacts expressing or condoning violence? Would we find a use for such “toys,” in both play and life?

While it is uncertain whether a ban on military-themed toys and games would be productive in an overall culture of violence, there are clearly other strategies available as alternatives. These strategies include teaching children critical literacy, the development of awareness and understanding of one’s own thoughts (meta-cognition), and a focus on less strongly gendered toys, for both girls and boys.

The year is 2018. Luka is a grown man. As he plans his first big trip overseas, he decides to get rid of some of his possessions. Among them is a video game console with dozens of games, as well as his World of Warcraft CD, one of his favourites. Luka remembers briefly how happy he was when his father purchased his first gaming console for him, and the good times he had with his friends playing all those games. And the fights he had with his mother when she tried to get him away from the games. “Anyhow,” Luka thinks to himself, “time to let go.”

Military service is no longer compulsory in the old country. Luka goes to visit it with his sister. He receives a court document for failing to register with the army. She does not. The army has found a loophole: service is not compulsory, but registration is. Just in case. Luka declares that he is a pacifist. The army officer sneers at him, but cannot arrest him or kill him, as he might have in the past. All he can do now is roll his eyes and mumble, “Oh, grow up! Mama’s boy.”

Futurists warn against making predictions because our futures arise not only from past and present trends but also from chance, innovations, and human agency. Still, it is probably safe to forecast that as long as we maintain violence-based cultures we will continue producing and exchanging gifts of military-themed toys and games. This is a chicken-and-egg type of situation: culture influences the development and production of toys and games, which then in turn influence cultural values, personal and group identities, and the imagination of one’s own place in the community.

Peace-oriented families and communities throughout history have prioritised compassion, kindness, equality or equity, justice and fairness; and so they have created social technologies that transfer these values, instead of values of competition, individualism and dominance.

Fortunately, for those who wish to build peace-oriented families and communities, there are many toys and games that are in alignment with the alternative: peace culture. These toys and games send the message that conflicts can be resolved without violence, that killing and violence are not an acceptable means of conflict resolution, and that all genders have a responsibility to maintain these values. Peace-oriented families and communities throughout history have prioritised compassion, kindness, equality or equity, justice and fairness[4]; and so they have created social technologies that transfer these values, instead of the values of competition, individualism and dominance.

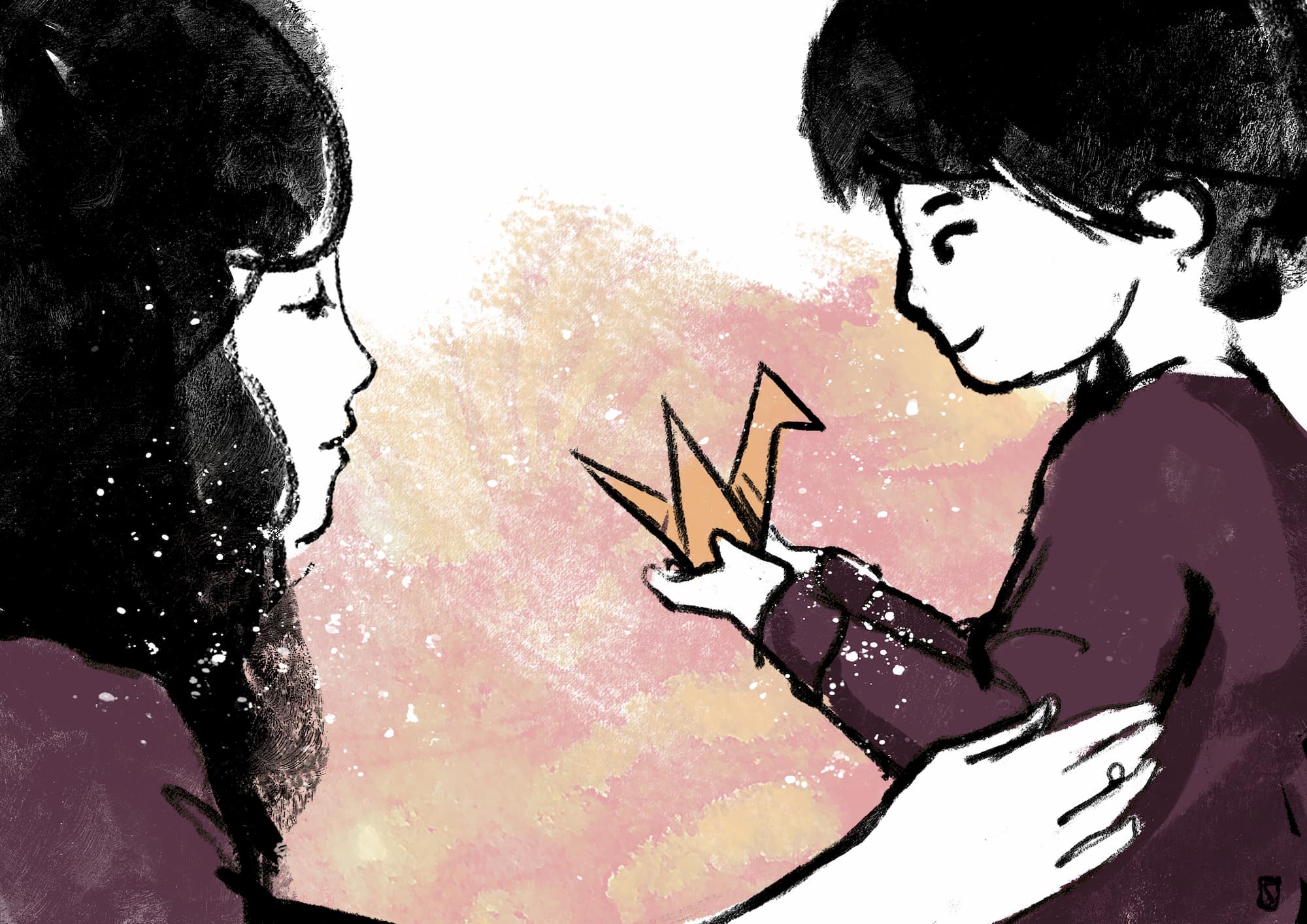

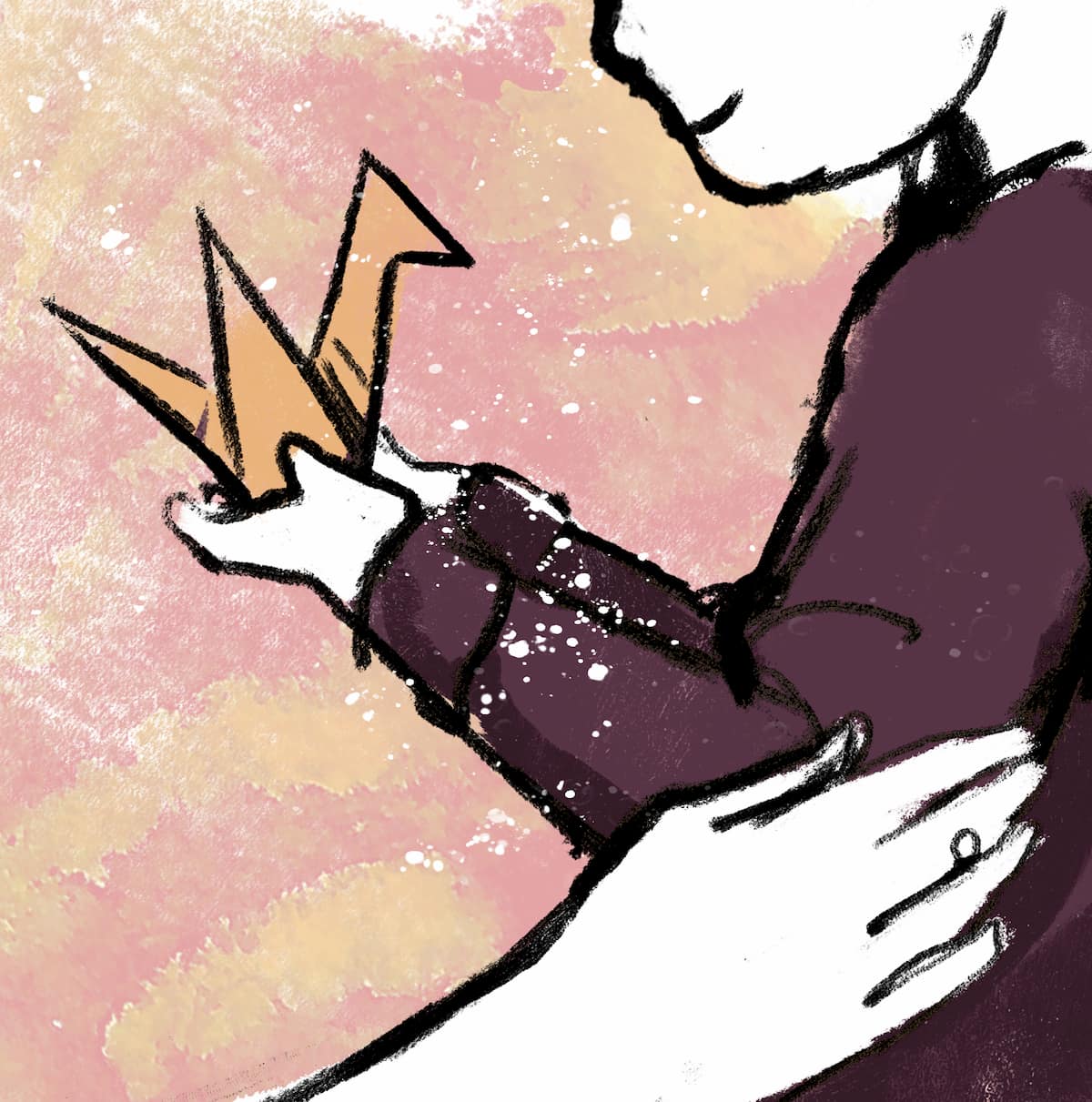

For example, the Sadako and the Thousand Paper Cranes stories, kits, and activities are used in many peace education programs in schools across the world. When children are gifted with a colourful piece of paper and invited to fold it into a paper crane, they are not only participating in an arts project or practicing their dexterity skills. In addition, they pay homage to a girl who was two years old when her home city of Hiroshima was bombed, and died at age twelve from radiation-induced leukaemia. The activity kits communicate the devastation that violence brings. Children learn about the legend of senbazuru: origami cranes are a symbol of peace, often used to memorialise the dead, and the Japanese legend says that anyone who folds a thousand paper cranes will be granted a wish. They read about Sadako folding paper cranes until she died, and about her hope and courage in face of extreme pain. They also participate in a global initiative carrying Sadako’s dream many years into the future. The colourful paper and the activities associated with it teach about hope, friendships, relationships, and about what humans have in common rather than what separates us. The values transferred are empathy and transcultural collaboration.

As with Sadako and the Thousand Paper Cranes, toys and games within traditional and contemporary peace cultures often do not rely on high-tech materials, plastic, mechanics, or virtual games – all signifiers of industrial and post-industrial societies. Rather, both traditional peace communities (pre-industrialisation) as well as emergent ecological ones (post-industrialisation) aim at choosing materials for toys and games that teach human connection with nature and are the least nature-taxing. Activities may include constructing one’s own toys from recyclable materials, or of donating items to toy and game libraries so that individual ownership of toys is replaced by sharing and cooperation. Garden and nature kits, as well, emphasise the importance of all living things and teach children how to take care of living beings and ecosystems. Additionally, peace initiatives encourage children to repurpose everyday items, so that they create their own toys using their imaginations; to investigate what toys and games are used in different cultures; to turn war toys into peace art; to conduct scientific projects with the goal of helping others; or to learn about solving problems through play. Some games marketed as anger management games focus on teaching emotional literacy, and cultivating inner peace and mental health.

At the same time, given the rise of computer gaming, in the past decade numerous individuals and groups, including the UN and UNESCO, have developed video games to promote peace and sustainability. PeaceMaker, for example, invites players to “succeed as a leader where others have failed” and “experience the joy of bringing peace to the Middle East.” BreakAway Games’ A Force More Powerful goes a step further, inviting gamers to “orchestrate a nonviolent resistance campaign from the ground up against dictators, occupiers, authoritarians and oppressive rule.” All of these games can be played by boys and girls alike, as peacemaking should not be limited to one gender alone.

Certainly, if we are to make changes to patriarchal “warrior societies” that separate human beings into mothers and soldiers, we also need to foster different gender dynamics. This does not mean turning women into warriors and disempowering men. Rather, it means changing the existing cultural framework that expects and accepts violent conflict resolution, prioritises dominance and aggression, and associates these with masculinity. Toys that reflect a shift away from that framework could be gender-neutral or gender-moderate; both frameworks are equally available to all genders. For example, Judith Blakemore’s key finding is that strongly gender typed toys are not optimal for developing children’s physical, cognitive, academic, musical, and artistic skills. Instead, gender-neutral or gender-moderate toys, such as those that teach spatial skills or house making and maintenance skills, science and building things, nurturing and care for infants, should be encouraged.

This does not mean turning women into warriors and disempowering men. Rather, it means changing the existing cultural framework that expects and accepts violent conflict resolution, prioritises dominance and aggression, and associates these with masculinity.

One country renowned for its society-wide emphasis on gender neutrality and gender equality is Sweden. Ranked third worldwide in gender equality, Sweden has paid parental leave for all sexes, a Minister of Gender Equality, and gender officers in public schools. Its capital, Stockholm, boasts a gender-neutral preschool, Egalia, where teaching aids include gender-neutral “emotion dolls” that teach children that all emotions are natural for all genders. Like any school committed to gender equity and social inclusion, it ensures that the stories it tells and the messages it sends accommodate more than the patriarchal nuclear family, working to include single-parent families, extended families, blended families, and those headed by same-sex couples. Story time in Egalia might include, for instance, a play in which two giraffes adopt an abandoned baby crocodile — a far cry from princesses saved by princes or boys slaying dragons (or other boys). While traditional fairy tale narratives often romanticise strict social and class hierarchies, the toys and games of peace culture and gender equity promote inclusion, equality and love, and subsequently better futures for us all.

In the past decade numerous individuals and groups, including the UN and UNESCO, have developed video games to promote peace and sustainability.

The way children play and the toys they play with will certainly continue to change and evolve, as they did in the past. In European towns nowadays, the girls no longer jump rope with lastiš, but play a multitude of digital games on their phones instead. It has been awhile since a European girl from a wealthy family sacrificed her doll at the altar of the gods when getting married in puberty, as she would have in ancient Greece. It has also been awhile since a boy or girl received an Encyclopedia Britannica. So perhaps we do engineer toys, play, gifting, gender, cultures and societies all the time. Whatever these artefacts and practices morph into will be in line with the cultural expectations of the time and place, both a cause and a consequence of the future we presently wish to create.

Children commonly mimic what they see adults do. They develop expectations based on what adults communicate to them. To weaken the power of violence-based cultural expectations and empower peace-based cultural frameworks instead, we need to communicate differently, and we need to do differently. In that sense, a humble toy is as good a place as any to plant the seeds of change.

The year is 2038. Mama’s and papa’s man, Luka, and his partner, Adeline-Zuelia, are celebrating the coming of age of their twins. Both Luka and A-Z are proud when told they are mama’s and papa’s children. So are the twins. The grandparents themselves are very excited about their grandchildren’s birthdays. The grandparents arrive early to assist with food preparation for the many people, young and old, who will attend the evening ceremony. Most partygoers are part of an intentional, peace-oriented community. The community teaches their children practical conflict resolution skills, how to be kind and compassionate, and how to listen to and respond to other people’s needs. The twins also grew up with the expectation that their gender should not limit the opportunities to feel and express themselves, for example, to like the colour they like, to play the sport they enjoy and to choose games that would challenge them. Like their parents and grandparents, they now commit to creating more gentle societies by becoming the nurturers and protectors of others.

The twins’ coming of age is marked by a new ritual created in their community: the gifting of their own toys. In this way, they step into a role of service to others in their community. Since they do not need to use things to fill the emotional gap within them, the items they transfer are few, but precious. Amongst them is their favourite childhood game: Imaginaire. This game encourages children to design alternative futures and then to choose the best possible world for themselves and others. Everyone plays with the present.

___

Dr Ivana Milojević is a researcher, writer and educator with a trans-disciplinary professional background in sociology, education, gender, peace and futures studies and Director of Metafuture.org. The information in this article was based on the paper found here.

Silvan Borer is an award winning freelance illustrator based in Zurich, Switzerland. He graduated from the University of Arts in Zurich. Silvan works on editorial and advertising illustrations as well as children’s books. His work is vibrant, whimsical and dreamy – he tries to express the elusive magic and profound beauty surrounding us. silvanborer.com/ https://www.instagram.com/silvanborer

___

Endnotes:

[1] Corrado, C. (2009). Toys. In J. O’Brien (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Gender and Society (pp. 839-841). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

[2]Corrado, C. (2009). Toys. In J. O’Brien (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Gender and Society (pp. 839-841). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

[3] Gilligan, J. (2001). Preventing Violence. New York: Thames and Hudson.

[4]Milojević, I. (2015). Breathing: Violence In, Peace Out. Brisbane: UQP.

Fascinating – thank you.

(I’m looking forward to giving Peacemaker a try!)

The issue of gendered toys has been really prominent in the UK for a while – two years ago I spotted a toy vacuum cleaner in a supermarket. No prizes for guessing which gender-presenting person was pictured wielding it…

The whole discourse around gender (and sex) in society needs to be revisited, and constantly challenged. Small moves have been made around gender-presentation equality in advertising, but does it go far enough?

The reinforcement of traditionally understood gender roles is continuous and ever-present, and this of course fits into what toy (or toothpaste packaging) one chooses for child A versus child B.

When we also layer issues such as mental health in, the drive to create empowering play (rather than stereotypical play) becomes ever more vital – because if a child feels more drawn to an unstereotypical toy, their identity is then questioned by others at a vital stage in their development.

At a social level, peace is an excellent thing to aim for. At a personal level, I’d suggest it’s mental health and long term health & wellbeing which are in the mix too.

It would be interesting to hear Dr. Milojevic’s thoughts on this point, Neil! Thank you for sharing.

Thanks for your comments Neil. I think it is really important to raise and discuss mental health and long term health and well-being in relation to our gender identities, so thanks for taking the initiative.

The research is quite solid in two respects: (1) multiple gender identities have existed through time and space, and these identities are malleable, (2) if a society restricts our freedom of expression and pushes toward limited gender identities our mental health suffers. We know, for example, that in homophobic societies attempted suicide rates and suicidal ideation among LGBTQ people are high. But in the context of intolerant societies even ‘the most powerful’ suffer. Too many men commit suicide as a result of not fitting into, or failing to match, the ideal of hegemonic/dominant masculinity.

The rate of PTSD and suicide among soldiers, for example, is also very high. Moreover, indirect deaths among men are often related to accidents which are connected to risky behaviours (i.e. road accidents, extreme sports) – some of those are behaviours which are somehow meant to ‘prove’ ‘the top dog’ type of masculinity.

Women, on the other hand, are encouraged to suppress anger, and accommodate others, which, not surprisingly, leads to a higher rate of depression among them, as compared to men. This very brief discussion, of course, only scratches the surface.

The main point I am trying to make is that multiple gender identities are not going to go away if a society is harsh and punitive towards those outside of the narrow norms. The only thing such harshness achieves is, as you remark, the negative long-term health and well-being effects.

Good luck with the Peacemaker game. Sadly, I believe many of the games I mention are now ‘historical examples’ and no longer available. Such is our (global?) culture of violence – it seems it is making it rather difficult to economically sustain the alternative, peace culture based games (and behaviours?).

Thanks for continuing the dialogue, Ivana! LGBTQ+ identity is one of my ‘specialist interest areas’ (lived experience as a gay man and professional experience working on Diversity & Inclusion initiatives within the LGBTQ+ space), and I absolutely agree about the malleability of identity.

Within the workforce, we see ‘filters’ applied by LGBTQ+ folk to fit in negatively impacting workplace performance, so even at that relatively microlevel, it’s possible to see how those ripple effects would influence experiences outside of the workspace.

Risk taking behaviours and/or non-optimal behaviours (such as smoking, drinking, illegal drug use etc) are also higher amongst the LGBTQ+ community. Off the top of my head I’m not sure if this is as a mask for mental health issues or a consequence of trying to fit into an idealised/imagined (and culturally reinforced) narrative of what it means to ‘fit into’ one gender or another.

To the point about male suicide, my partner & I contributed to the Kickstarter for “Steve: A documentary about male suicide” (https://www.stevedocumentary.com/), and were fortunate to interview the writer/director for a podcast we ran. Very sobering, and so very eye opening – it’s gone on to create huge amounts of conversation and, we hope, create positive support. It’s definitely worth a view if you have the opportunity.

I did try the Peacemaker game but it didn’t work on my newer Android system, unfortunately. I wonder what it would take to get the code updated?