Thresholds Issue ❷ ↓ Feature

Being Together with Strangers

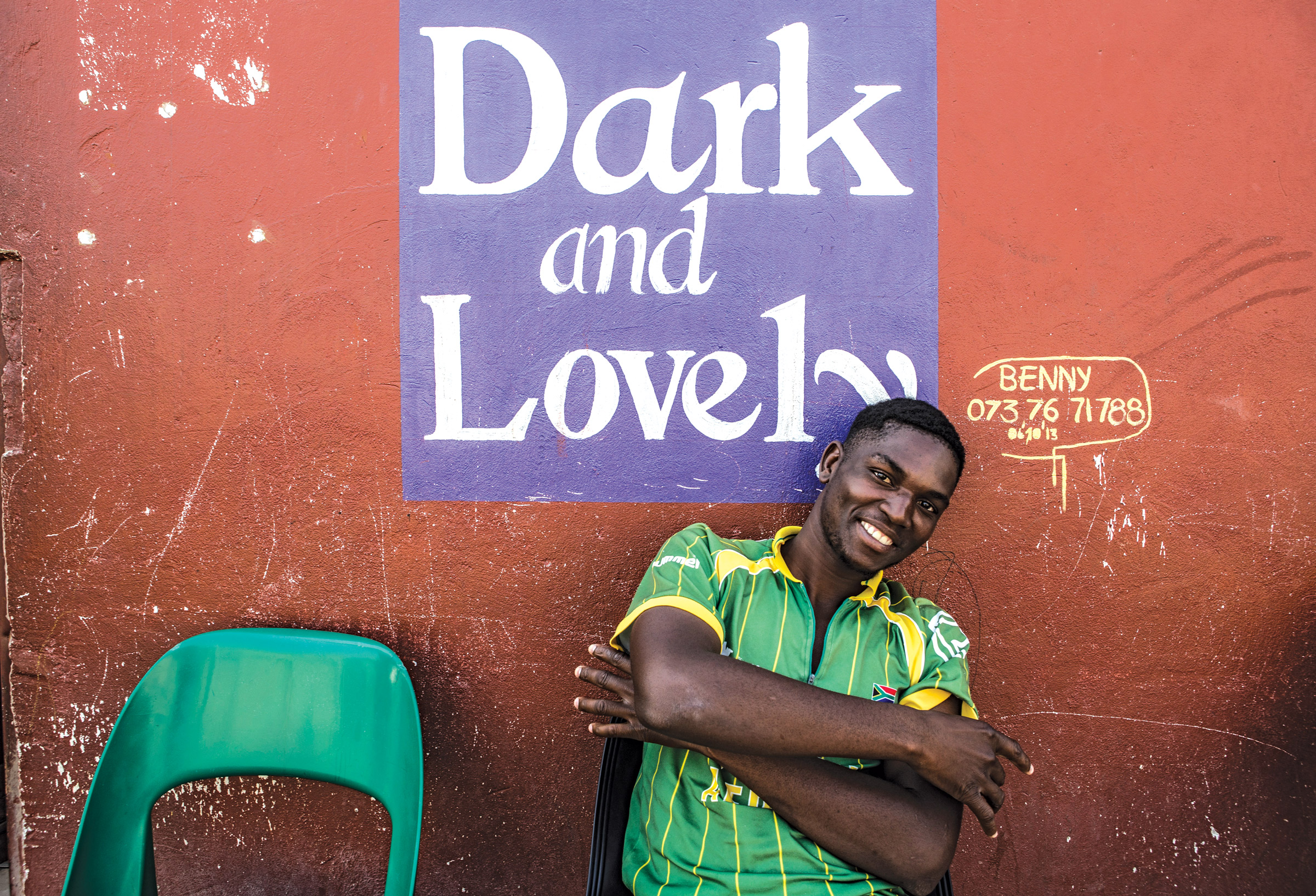

Post-apartheid Johannesburg is often misunderstood as a city lacking connections across divided spaces and lifeworlds. If we pay close attention to urban everyday life, though, we can see that people living in the city are engaged in constant creation and appropriation of social spaces. Some of these spaces serve for social enclosure, but others also for social encounters.

City of Connections

The very first time I met Sbongile, 28, she was sitting on the bed in her mother’s shack. She had dressed herself carefully for the meeting with me, a foreign anthropologist. She comes from a very poor household which is based in two locales. Her mother and her younger brother usually stay in this shack in Alexandra Township, Johannesburg. The place that they consider home, however, is in rural KwaZulu Natal, where the rest of the family – her sister, niece, and grandmother – live in a shack settlement. Sbongile travels between the two homes, adapting to job opportunities and family conflicts. Her mother, Zuzile, 46, is the only person in the family with regular income. Towards the end of apartheid, Zuzile moved to Johannesburg to find work. Since then she has been working as a domestic worker in Johannesburg’s northern suburbs. She looks after the children of white middle and upper class families, while her own children grew up under the supervision of Zuzile’s mother and relatives.

“Me and my sister, we never lived with our mam in one place,” Sbongile says. “She was always working [in Johannesburg], since we were kids. It was hard; we had to wait for her to send money home, so that we could buy food.”

Sbongile and Zuzile’s story is similar to many of Alexandra’s residents. Johannesburg, today the economic powerhouse of the Southern African region, came into being at the end of the 19th century after gold was found in what turned out to be the world’s richest goldfields. The promises of the “Egoli,” the city of gold, attracted people from all over the country, the continent, and the world, transforming the dirty mining camp into the largest city in sub-Saharan Africa. The city’s white political and economic elite, the constructors of apartheid, thought that cities in South Africa should be white spaces where black bodies were tolerated only as workers. Black mine workers were contracted for limited time periods to work and live on the mines, and then they had to return to rural areas. In his seminal work The Production of Space (1974), Henri Lefebvre famously criticised the idea of space as a container within which social practice takes place, stating that it is actually social practice that create spaces. Cities are often wrongfully conceptualised as closed spaces with absolute boundaries. For post-apartheid Johannesburg, it is the movement of money, people, and culture between rural and urban areas that has created the city space.

A Heritage of Resistance

During apartheid black people were forbidden from living in the city. In spite of that, people resisted, were creative, and found ways to settle in urban spaces outside of the control of the state. Alexandra Township emerged as such an urban space. It was founded in 1912 as a “freehold” township by a real estate investor who sold the plots to a racially mixed population. When “white” suburbs around Alexandra grew in the 1930s, their residents soon started to demand that the “black spot” be removed. Alexandra’s residents successfully fought off eviction several times. This township was not state-planned or state-initiated, and it has always been difficult for the state to control. Many “illegal” black people found refuge in Alexandra, arriving from diverse rural and urban areas, turning the township into a physically and socially dense space with over 350,000 residents.

Because of the highly unequal investment in urban infrastructure during apartheid, electricity, roads, sanitation, and schools are still insufficient to meet the needs of the residents of Alexandra. Post-apartheid investments in infrastructure could not undo this imbalance.

For Sbongile and her family, this situation is not solely a disadvantage. On the one hand, living in Alexandra is harsh because of the frequent power failures, the lack of proper toilets, the threat of rape and other crimes in public spaces, and the dirt on the streets where their children play. On the other hand, the township provides them with affordable shelter: because building laws are lax, they can rent an illegally built shack in the backyard of their landlord’s house for an affordable price. In addition, Alexandra is relatively close to everything, so Zuzile can walk to her workplace in nearby Linbro Park, where she works as a domestic worker.

Alexandra’s residents successfully fought off eviction several times. This township was not state-planned or state-initiated, and it has always been difficult for the state to control. Many “illegal” black people found refuge in Alexandra, arriving from diverse rural and urban areas, turning the township into a physically and socially dense space with over 350,000 residents.

While many outsiders and rural migrants see Alexandra as a place of poverty, crime, and despair, those who have grown up in the township consider it a home, a space of identification and even pride, and a space of leisure and creativity. It is famous for having a lively and diversified nightlife, which attracts residents from other parts of the city. Zuzile and Sbongile, though, know little about the lively urban culture in Alexandra; often moving between the rural home and the urban township, they would rather invest in relationships back home, not least because they mistrust the urbanites, fear the violence, and don’t want to get involved with drinking alcohol, which they see as a socially destructive vice. While many of their neighbours drink on Sundays, Zuzile takes her children to church.

Her church, an African Independent Church, exists both in nearby Pretoria as well as in her rural home and provides a social home to the family. In Johannesburg, religion and other metaphysical beliefs are key to how people make sense of the city and deal with social differences. Churches are not only places of prayer but also spaces where lifestyles are formed. Avoiding drinking and partying can make churchgoers less involved with social life in the immediate neighbourhood, but can also offer a form of protection from social ills. Going to church can be seen as a form of social enclosure through which city dwellers are able to retreat from the social relations and spaces they consider dangerous into morally safe and trustworthy environments.

A Heritage of Privilege

In cities marked by high levels of urban violence, poverty, and inequality, being together with strangers can make people anxious. Living in a city means having to either tolerate regular encounters with strangers or keeping apart and enclosing oneself. This tension is often expressed in the way a city is built; using public spaces to bring people together or boundaries like walls to keep them apart. But as Zuzile’s case shows, residents also use social means, like the choice of a religious lifestyle, to create social boundaries between themselves and others.

Johannesburg is famous for its walls and separated spaces. Apartheid created a highly segregated city. Alexandra is separated from the surrounding white suburbs by an industrial fringe and roads; one of them the national highway N3, which borders sections of Alexandra built after 1994.

Behind the highway and a large waste dump, I had the opportunity to meet the members of a very different community found in a neighbourhood called Linbro Park. One of them, Roger, lives on a large property. Like Zuzile, Roger is a migrant to Johannesburg, although he is from outside South Africa’s borders. His parents were German, and he grew up on a farm in Namibia. He worked all his life in real estate, and in the 1980s, he made his dream come true and bought his property. Most of his neighbours also have European origins. Some of them moved to South Africa in the 1970s, when the apartheid state wanted to attract European professionals to help the economy and attempted to construct a white country, paying to fly Europeans to South Africa. The majority of Roger’s neighbours are self-employed and have their own businesses, which range from agricultural (plant nursery) to small manufacturing and to the tertiary sector (law, accounting, and tourism).

In contrast to Alexandra, where space is scarce and families like Zuzile’s share small shacks, land is abundant in Linbro Park. Roger’s property is about 2.5 hectares and is zoned “agricultural” by the municipality. Linbro Park has, even for the spread-out northern suburbs, an extremely low density. Its surface area of about 5 km2 (500 hectares) is home to at most 1000 to 2000 people.

“It’s just farmland,” says 34-year-old Peter, a resident of Alexandra. “You find somebody living in 10 hectares alone, and there is nothing. And you know, within one property, you could at least put 50 houses; you could take 50 families from Alexandra to live there.”

Similar to Alexandra, there is little public infrastructure, not because the apartheid regime did not want to invest in the neighbourhood, but because the residents themselves wanted their spaces to keep a “rural flair” and, for example, opposed the installation of street lights. Today, residents still refer to their lifestyle as “country living in the city,” by which they mean that they live close to urban amenities, but in a spatial environment reminiscent of rurality. Living on a large property gives them a feeling of freedom and a privacy that has protected them from the rapid changes that South African society has experienced. Their way of life has been shaped by their childhoods, when many of them lived on farms.

Dave, 62, lives in Linbro Park. “You must understand,” he says, “I was born on a farm, and I was raised on a farm. I have been a farmer’s son. To live in a little box on top of another is not my scene. And I see it, when I go to Europe, I see how there is no space. I come back to Africa and I think, ‘Oh, we are very lucky.’ I need the space, the outdoors.”

Identity, horse riding, and nostalgia.

The idea of “outdoor” is also lived by Linbro Park residents through their hobbies, among which horse riding is the most important. When I asked residents in Linbro Park why they moved to this area, many explained that the large property allowed them to keep horses for their children to ride. In the 1970s and 1980s, the neighbourhood used to have an active, leisure-based lifestyle that revolved around horse riding and other Victorian sports, namely tennis and ballroom dancing. Horse riding was not solely a means of physical exercise for the children. Looking after a horse, riding out on horseback, and participating in competitions also involved parents, who took the opportunity to socialize with their neighbours. Horse riding became an important element of country living in the city—part of the collective and individual identity of Linbro Park residents.

“I moved to Linbro Park because of the horses,” says Sarah, 66. “My children were into horse riding. And I just loved living here, I love the quiet. Even the library used to have a hitching point…I still have a picture of my daughter and her tied-up pony in front of the library when she went to get a book for school. It was lovely. But as they say, progress comes along, and all your good living goes out the window.”

Nowadays the horse riding community has shrunk considerably. Parents have retired, children have moved out. When I visited Sarah for the first time, she showed me the former horse stables on her large property. She explained that they had transformed them into rental rooms. Linbro Park has ceased to be predominantly white. Many property owners host tenants from racially and ethnically diverse lower middle-class and middle-class groups. There are, and have always been, a considerable number of black domestic workers, gardeners, and handymen who live and work in this neighbourhood.

Linbro Park is changing rapidly. Social life has moved from shared communal spaces into the virtual spaces of Google Groups and WhatsApp, where residents exchange information and complain about crime, illegal dumping, and speeding cars. Real estate developers and the municipality are interested in putting the land to more intensive use. At the northern and southern boundaries, warehouses and office complexes have replaced the horse farms. Many residents are keen to sell their land, as they fear that the municipality will construct housing for Alexandra’s poor, which they believe will lead to crime and reduce property prices. For many, the investment in the land constitutes their financial security for their retirement. Others claim that they want to stay as long as they can, fearing that they won’t find land where they can continue their semi-rural, semi-urban lifestyle.

“Linbro Park is changing, and it is changing quite rapidly now,” says Sarah. “It is starting to lose its little farm sort of community atmosphere. When they opened the business park, traffic started to pick up, so it’s dangerous to ride horses on the streets now. You can’t stop change. As much as you would like to. I always laugh when they say ‘it’s progress.’ Progress for me is somehow moving forward to something better. I say, ‘This is not moving forward to something better, this is ruining something beautiful for something uglier.’ Those warehouses are such ugly buildings! For 30 years, we didn’t know what was gonna happen to this area. We still don’t know what was gonna happen. So I enjoy it while I can.”

Similar to Zuzile’s family’s retreat into the church, the Linbro Park residents retreat into nostalgia on their large private territories—a form of social closure from the rapidly changing urban society around them.

Intersections between diverging worlds

How urban dwellers experience the urban is greatly influenced by their social background. We always need to ask ourselves: whose city–whose urban experience—are we writing about? Not only Linbro Park, but also Alexandra is highly differentiated; the township is marked by internal social and political divisions, which go beyond standard categorisations of class or ethnicity.

Everyday life in suburbia follows different patterns than in the township. While these lifeworlds may seem so different and far apart, they are also deeply connected and interdependent, especially economically. Zuzile has been working for a white family in Linbro Park as a domestic worker for more than 10 years. Every morning she walks one hour from Alexandra to Linbro Park, where she cleans and cooks. When her employer’s children were still living at home, she looked after them while their parents were at work. Most of the wealthy families in Linbro Park employ domestic workers who are usually black, and who live on their employers’ properties, or commute from Alexandra or other townships. Working conditions during apartheid were appalling for domestic workers. Scholars and domestic workers themselves often compared it to slavery. Since the end of apartheid, working conditions have improved considerably for many, but the structural inequalities have remained.

Everyday life in suburbia follows different patterns than in the township. While these lifeworlds may seem so different and far apart, they are also deeply connected and interdependent, especially economically.

In these everyday interactions, workers and employers learn about each other’s life-worlds. Domestic workers learn about the intricacies of domestic and neighbourhood life in the affluent suburbs, often knowing them better than their employers, who are away during the day. The employers also get glimpses into the everyday lives of their domestic workers. However, the relationship is still marked by deep inequalities, which lead to a reproduction of prejudice, not its reduction. Although many of the domestic workers work and even live for years in Linbro Park, the white residents do not treat them as neighbours or as members of the community. They are seen as workers whose right to be in the neighbourhood is linked to employment.

Care work is highly personalised, and the white family’s attitude towards their domestic workers is usually deeply paternalistic. Many employers claim that their workers are “part of the family”; they give them additional money if there is a family tragedy, and they donate old clothes, laptops, and food to their workers. Domestic workers, like Zuzile, are often grateful for the help, upon which they are highly dependent, but they also begrudge their low salaries and hand-me-down gifts. The creation of paternalistic ties can be seen as a strategy on the part of both domestic workers and employers to create more security in the unequal relationships and an attempt to make them more personal and bearable.

All the mall's a stage

In comparison to the deep inequality and dependence which many domestic workers experience in the workplace, being together with white, affluent city dwellers as consumers at the mall is experienced as a form of freedom. Domestic workers have explained to me that at the mall, they feel “free” to interact with white people in different forms. Domestic workers observe white women studying the prices just like them, and then engage in chats about rising prices. Although they have widely different resources, shopping together can create a linking encounter, as consumers and as women, who share not the same, but comparable, worries about buying appropriate foods for their families.

When she goes to the mall, Sbongile can forget for a couple of hours the hardship of her troubled life. “Whether I am from the suburbs or the township,” she says, “I feel like we are all the same at the mall, because we are there for the same purpose—we are there for shopping.” She has impeccable taste, and although she has little money to spend on clothes and hair, she knows how to dress up and often receives compliments from complete strangers. The shopping mall, a commercial public space, allows her to pretend to be someone else for a couple of hours and forget the personal misery and conflict that emerge out of the cramped living conditions and poverty in Alexandra Township.

Especially for young, poor urbanites in Johannesburg, shopping malls are sites of experimentation, playfulness, and deceit. Young women from Alexandra sometimes go with friends to malls, where they look at dresses and comment how they would look on their friends, pretending they could buy it. Others try on fancy dresses in dressing rooms at clothing stores, use cell phone and cameras to take pictures, which they then put on Facebook. The mall is also a place of com- petition among youth equipped with very different resources. Good taste in styling one’s body cannot be bought, and many young women manage to look good and receive compliments from strangers, although they can only afford cheap clothes.

“They don’t even look good in what they are wearing, although it’s expensive,” Sbongile says. “Now I am wearing things that cost…R150. But I am looking good and I am feeling good. You may have money, but you are not better than me.”

City of contradictions.

In many cities across the globe, walls—around affluent houses, around gated communities, around shopping malls—have become the symbols for the massive urban divisions and inequalities Johannesburg is one of them. Apartheid created economic inequality and segregated cities. Public life in the suburbs and townships is understood as divided and evolving in different spaces: privately owned shopping malls are usually seen as the public spaces of the suburban middle class, while the public life of poorer urbanites becomes visible in public spaces owned by the state, such as parks and squares. Everyday life in Johannesburg, however, is not that straightforward. Living with inequality and diversity has certain advantages: mingling with people who are different can be enjoyable, like at the shopping mall. The lifeworlds of Linbro Park and Alexandra—of Roger and Sarah and Zuzile and Sbongile—are so far apart, separated by a highway, but nevertheless connected, socially and economically. Their worlds are interdependent. Places like Alexandra are not simply poor but are spaces of agency, creativity, joy, and hope. Shopping malls not only reduce all people in a city to consumers but also provide them with new stages upon which to play with their identities. Domestic work is a site of exploitation but is also a source of mutual support and interdependency.

Divided cities are not only about social closure but also about encounters, which have the power to reach across difference, and defy expectations.●

—

Barbara Heer is a social anthropologist engaged in academic research, teaching, applied work and politics. barbara.heer@unibas.ch. If you would like to read the original research for this article, click here.

Mark Lewis is a South African photographer, currently living and working out of Johannesburg. He has participated in many exhibitions and has had solo shows both on the continent and abroad. marklewisphotography.com