The Truth Equation

The scene is a graduate class in quantum physics at UC Berkeley. Seth Border, a brilliant and popular but undisciplined graduate student, stands up and starts arguing that the equation on the blackboard, the one to which his professor has devoted an entire career, is wrong. The calculations are right, Seth argues in complicated language, but the implication is wrong. The professor retorts pompously that all the other experts agree with him, insults Seth’s clothing, and reminds the class of his authority. In response, Seth quotes Oliver Wendell Holmes (1841-1935), George Savile (1633-1695), Amos Bronson Alcott (1799-1888), Gotthold Lessing (1729-1781), and Goethe (1749-1832), before presenting his own equation, one that proves the existence of God, humiliating the professor in the process. Seth walks out of the class, leaving the professor speechless and impotent in the face of Seth’s brilliance and popularity. The equation Seth has written on the board gives him the power to see the future.

This is one of the opening scenes in the novel Blink of an Eye (2002), a thriller by author Ted Dekker. Dekker is a very popular American conservative evangelical Christian author whose books are meant to appeal to mainstream audiences. In Blink of an Eye, Border goes on to use his newfound powers to rescue a Saudi Arabian princess, Miriam, who is fleeing a forced marriage. She’s on campus to ask a Middle Eastern Studies professor for help. The professor, another woman, advises her to go through with the marriage and then calls the prospective groom’s hired kidnappers. As a former graduate student, I find all of Dekker’s university scenes extremely implausible. As a person who studies fantastic literature, I believe that Dekker’s book and other works of evangelical fiction can tell us important things about American conservatism and its relationship to information, expertise, and the truth.

When authors set the rules of the world, what they think those rules are or should be says a lot about them, their culture, and the people they’re writing for. White evangelical American Christian fiction deals with information in ways that are often recognizable in contemporary conservative American political discourse.

As I write, wildfires are raging on the American west coast. When Wade Crowfoot, California’s Secretary for Natural Resources, told US President Donald Trump that the key to protecting Californians was addressing climate change and “working together with that science,” the president told him, “Well I don’t think science knows, actually.” From climate change to COVID-19, American conservatism is skeptical about scientific consensus, and it’s a deadly trend.

The extreme polarization of American political discourse is a threat, not only to America, but also to other countries that are influenced by American culture and, for whatever reason, depend on America’s continued functioning as a democracy. The left accuses conservatives of supporting systems that oppress the margins, even in the face of a landslide of evidence. The right accuses liberals of using their stranglehold on universities and the media to indoctrinate young people into a left-wing agenda that undermines the foundations of America, attacking the centre and their hard-won status quo in favour of the undeserving margins. The left tends to see widespread problems as rooted in systemic inequalities. These injustices can and should be addressed by evidence-based policy changes. The right, on the other hand, tends to see widespread problems as being rooted in individual weakness. It seeks to solve them by encouraging individual virtue: policy changes won’t have any effect on the human heart, and might in fact discourage virtue by shielding people from the consequences of their actions, and making them comfortable enough as they are.

A glance at American news sources on opposite sides of the political spectrum shows disagreement on what the facts are in any given situation, and how to interpret those facts. But a bigger problem, as I will show here, is that left and right no longer agree about what facts are made of—what constitutes true information, where it comes from, how we recognize it when we see it, and how we test it when we are in doubt.

I’m a Canadian, so the culture I’m writing about is both outside of and close to my culture. Some of my conclusions apply inside of my own country as well, and some do not. And neither left nor right nor evangelical are one single thing; they are clusters of ideas and tendencies and thought patterns held by diverse and complex people. People on all sides of the political spectrum get their information from a variety of sources, none of them perfect. Information and misinformation can be deliberately weaponized and commodified, and this is a serious issue, but for now I’d like to talk about broad tendencies in how people evaluate that information.

My conclusions only apply to white evangelical Christianity, which is different from Black American evangelical Christianity. In addition, American conservatives and white American evangelical Christians are also different from one another in many ways, though there is a significant amount of overlap. White evangelicals are a quarter of the electorate, and 81% of them voted for Donald Trump—and there is a great deal of intellectual cross-pollination between the two groups, with similarities in the ways information and authority are discussed in white evangelical fiction and American political conservatism.

The extreme polarization of American political discourse is a threat, not only to America, but also to other countries that are influenced by American culture and, for whatever reason, depend on America’s continued functioning as a democracy.

Where do we get the information we rely on in order to conduct our lives? We get it from friends and family, from social media, from news sources and sources of entertainment that engage with the news (talk shows, YouTubers, stand-up comedy, listicles, and the like), and from official communications from governments and organizations jockeying for our attention and our support. We tend to trust sources that fit best with what we already understand about the world. Confirmation bias can stop us from absorbing challenging ideas, but it’s also useful and necessary, especially when we have a lot of sources and limited bandwidth. It’s work to track down and evaluate the raw data that the news is made of. Not everyone has the time, energy, expertise, or access, so it makes sense to delegate that work to people you trust to share your values: news sources that interpret events in ways that make sense to you, science popularizers whose job it is to turn scientific research into accessible articles, public intellectuals such as Neil De Grasse Tyson or William F. Buckley, bloggers who share your perspectives and interests, and friends who claim some authority on the topic. One important set of values I’ve discovered that is shared between evangelical Christians and the wider American conservative movement is orientation to information: how one recognizes the truth.

THE TRUTH IS RADICAL

When I say radical, I’m using its original definition, as in “from the roots,” foundational, rather than the way we frequently use it today, meaning extreme. To understand something’s nature, this white evangelical and conservative principle says, we should examine its origins. Correct positions can only come from correct hearts and minds. In evangelical Christianity, salvation is a profound change, the most important experience in a person’s life: even if a person grows up around white evangelical teaching from the start, and has done all of the right things, without the experience of salvation they can’t have real joy, real goodness, or real wisdom. And while American conservatism does not require a conversion story, it shares white evangelicalism’s concern about purity of origins.

In Frank Peretti’s 1989 supernatural thriller Piercing the Darkness, which won the Evangelical Christian Publishers’ Association’s Gold Medallion Book Award for fiction in 1990 and concerns a satanic plot to take over the public school system, even the evil liberal conspirators who don’t agree with the protagonists about anything agree about the importance of origins. The villains’ goal is to indoctrinate children as early as possible by infiltrating the educational system and teaching yoga and mindfulness exercises that leave the children open to possession by demons. Well-meaning teachers refer to the demons as “inner guides,” because without a solid Christian foundation, liberals cannot perceive their true nature. They are incapable of understanding the world or themselves, and they tolerate or even embrace world religions and New Age thought without realizing that these are all a front for Satanism. The plot centres on the conspirators’ attempt to cover their tracks by assassinating the woman who developed the Satanic curriculum.

For people who follow the conservative evangelical program of truth, in politics, the truths come from the Bible (and many non-religious conservatives who don’t believe in salvation argue that the Bible is still a good source of truth and values) but also from America’s founding documents—the Declaration of Independence, the Bill of Rights, and the Constitution. American conservative thought often gives these the status of quasi-sacred texts. In Piercing the Darkness, one of the good guys, a Christian lawyer, scoffs at the notion that the American constitution could be “a ‘living document’ that can be reinterpreted by the courts as society continues to evolve morally.” (Note the use of the word “evolve” for wrongheaded thinking.)

The Puritans who arrived on the shores of what would become New England originated the idea that America was a chosen nation—the list of chosen nations beginning in order with Israel, then England, and finally America, the final chosen nation to end all chosen nations. That idea has persisted in American political culture. John F. Wilson noted in 1979 that American exceptionalists of all political orientations never doubted that America was a chosen nation; the disagreement was about what it was chosen for. Some white evangelical Christian thinkers, such as the late Tim LaHaye, husband of Concerned Women for America president Beverley LaHaye and co-author of the bestselling Left Behind novels, have argued that America’s founding documents were divinely inspired.

What does it mean to read political documents in the same way as sacred texts? For one thing, as the lawyer says in Piercing the Darkness, modifying these texts, or reinterpreting them to suit the needs of a changing society, introduces dangerous errors. If these documents expressed truth at the beginning, then every change takes them further away from truth, especially when those making the changes are not right-thinking people. And the intent of the people who wrote them isn’t just important; it might be the most important thing. This is one reason why American conservatives who argue about their Second Amendment right to bear arms talk about what the Founding Fathers would have wanted, when the left suggests that present-day conditions make gun control desirable.

One characteristic of true knowledge is that it is simple, clear, direct, and accessible. An author introducing nuance or complexity to their writing is, on the other hand, seen to be introducing deception and elitism.

Another example of the concern with roots is the conservative attempt to discredit and (successfully) defund Planned Parenthood by bringing up the alleged racism of its founder, Margaret Sanger. Anti-choice activists often quote a sentence from Sanger’s December 10 1939 letter to Clarence Gamble: “We do not want word to go out that we want to exterminate the Negro population, and the minister is the man who can straighten out that idea if it ever occurs to any of their more rebellious members.” However, the project she describes in this letter was actually undertaken with the help of pioneering sociologist and prominent Black activist W.E.B. DuBois, and the passage above was about concern about misconceptions, rather than a description of any secret agenda. Sanger was working in the first half of the twentieth century, when the cultural landscape looked very different from today, and she engaged seriously and critically with a lot of ideas that today we would dismiss out of hand. It seems that by proving racism in the organization’s founder, conservatives expect to expose the present-day organization itself as morally unfit and unworthy of support, to the point that Planned Parenthood has removed Sanger’s name from its New York City headquarters. However, it is safe to say that the people who use Planned Parenthood do so not because they approve of its origins or its founder, but because it provides important healthcare services for them.

THE TRUTH IS CLEAR AND ACCESSIBLE

As political analyst Thomas Frank outlines in his 2004 book What’s the Matter with Kansas?, American Republicans have found success by convincing working-class voters that they are the party of authenticity, plain-speaking and hardworking, and that the Democrats are the party of the latte-sipping liberal elite—even though Republican deregulation and cuts make it easier for large corporations to exploit workers while at the same time dismantling the social safety net designed to protect them. The election of Donald Trump isn’t an aberration; it’s the result of a decades-long trend. His blunt, scattered, uncouth, and often incoherent utterances are interpreted as signs of spontaneity, authenticity, and courage—an antidote to liberal arrogance and snobbery.

Although the most dire imaginings of American evangelical Christians—that America is on the brink of outlawing Christianity, that Christians will be rounded up and punished for their beliefs—are influenced by apocalyptic prophecies and fiction more than actual events, white conservative American evangelical Christians aren’t imagining things when they see themselves as the objects of liberal derision. For example, their fiction has a reputation with the larger literary establishment for being simplistic and poorly written. This is partly because what conservative evangelicalism values in writing and what the literary establishment values in writing are in opposition to each other. To literary pundits, good literature can be multivocal, ambiguous, ambivalent. Good literature can use figurative language to engage our senses and deepen our understanding, shed light on the darkest parts of human existence, and challenge the foundations of our cultures, identities, and knowledge. If two different people read a novel and come away with two different interpretations, or if the novel we read at twenty-four is gloriously different when we reread it at seventy-two, then the author has done a good job, having woven a rich tapestry that speaks to the complexity of human experience.

Another of the key characteristics of true knowledge in white evangelical Christianity and American conservatism is its staying power. The truth does not change, and anyone who suggests that it might flirts dangerously with moral relativism.

Evangelicalism regards texts differently. For one thing, it is fundamentally democratic: everyone will be judged by God, and the stakes are no less than the eternal destiny of one’s immortal soul. Mark Noll, in his 1994 book The Scandal of the Evangelical Mind, stresses that evangelicalism comes from the same Protestant movement that established universal education as an ideal. The gospel should be accessible to anyone and everyone, regardless of age, gender, ability, education, or social status; and good fiction, of course, should point readers to the gospel.

This is why white evangelicalism is also concerned about the secularization of American society. More than one author has used their fiction to argue that secularism is a front for Satanism. One reason for the growth of the conservative Christian evangelical fiction publishing industry was an increasing anxiety that mainstream media was leading consumers astray.

Even a secular author’s declaration that their text does not have a single, intentional meaning is suspicious. Multivocality, ambiguity, ambivalence, and figurative language are, at best, tools that cloud a text’s true meaning, and at worst, satanic traps.

So, to someone who follows this white evangelical program of truth, one characteristic of true knowledge is that it is simple, clear, direct, and accessible. An author introducing nuance or complexity to their writing is, on the other hand, seen to be introducing deception and elitism.

THE TRUTH IS INTUITIVE

If the truth is accessible and uncomplicated, if it does not require training or resources to access, but only a heart that is in the right place, then it follows that gut instincts are valuable in making decisions.

In addition to Blink of an Eye and other works, Ted Dekker has written the Books of History, a series consisting of the Circle science fiction tetralogy, the six-volume Lost Books YA series, and the Paradise trilogy of horror novels, which are interlinked in ways that make reading all thirteen books necessary to fully understand what is going on and what motivates characters. Characters in these novels often make gut-level decisions that defy logic, practicality, and sometimes the direct orders of their superiors. In Chosen (2007), an untrained and unqualified teenager is selected as a soldier for his ability to “think with his heart”; in the sequel, Infidel (2007), he then leaves a mission, stranding his commanding officer in the desert, in order to rescue his mother. In Saint (2006) a paid assassin murders the man who hired him on a hunch . In Black (2004), a barista kidnaps a scientist and holds her hostage based on a dream he had. Even though the actions described are morally dubious at best, these decisions are made by right-thinking people in the right frame of mind, so they are deemed good decisions. Occasionally these right-thinking protagonists face worldly consequences for their actions, but these are very light; and more often, they are rewarded for their quick, intuitive thinking.

A major friction point between white evangelicals and the mainstream, and now conservatives and liberals, is science. The self-correcting nature of science means that the knowledge that comes from it is often changing. Evolution is the classic example of an evangelical conflict with science. However, the wider American conservative movement and particularly the Trump administration have seized on climate science, calling it a hoax. Progressive evangelical blogger Fred Clark writes that certain apocalypse-flavoured evangelical beliefs dovetail nicely with the agenda of the oil industry: in the 1990s Ford executive John Schiller assured green entrepreneur Jeremy Leggett that he wasn’t concerned about the impact of fossil fuels because the Earth was only ten thousand years old, and extreme weather and other signs of environmental devastation were signs of the End Times. In the past thirty years, climate skepticism on the American right has only solidified.

Science gets things wrong often, and communication about the results of scientific research has a lot of room for improvement. Still, self-correcting mechanisms such as peer review, the requirement to disclose conflicts of interests, and transparency about study design mean that results are continually being improved…unfortunately, for someone who believes that truth is unchanging, it also means that science is continually proving itself untrustworthy.

Gut instincts are useful in situations where decisions have to be made quickly in the absence of data, but decisions based on intuition do favour the status quo and unconscious biases. This is the case for people across the political spectrum, although the tendency is to talk about one’s opponent’s feelings and one’s own instincts. But like one of the protagonists in an evangelical novel, Donald Trump prizes gut instincts even above expertise, telling The Washington Post, “I have a gut, and my gut tells me more sometimes than anybody else’s brain can ever tell me.” Likewise, he credited gut instinct as the reason for his assertion that Obama’s birth certificate was forged, and a “hunch” for his assertion that COVID-19 is less deadly than the current numbers show. Bob Woodward’s new book makes it clear that even at the time, Trump knew otherwise, but it’s telling that Trump framed the lie as a “hunch,” knowing his supporters would find that persuasive. Policies based on misinformation have contributed to tens of thousands of deaths at the time of publication.

THE TRUTH IS UNCHANGING

Another of the key characteristics of true knowledge in white evangelical Christianity and American conservatism is its staying power. The truth does not change, and anyone who suggests that it might flirts dangerously with moral relativism. Returning to Peretti’s Piercing the Darkness, a well-meaning spokesperson for the antagonists of the novel explains to a character, “Obviously…the goal of education, true education, is not simply teaching generation after generation the same amount of academic content as a preparation for life—just the same old basics, as they say. The human race is evolving too fast for that. What we are more concerned with is the facilitation of change.” (Note that once again, evolution is linked with the villains.) Thinking from antiquity or the seventeenth through the nineteenth centuries, the kind of thinking Seth Border uses to argue against his professor in Blink of an Eye when he quotes George Savile and Gotthold Lessing, is interesting, but outside of conservative and white evangelical culture, it’s not the best source of true information and helpful insights about the world today.

If secular conservatism is willing to adopt the evangelical position on climate science, the process works in the other direction as well. An even more urgent site of disagreement between scientific consensus and American conservative culture is epidemiology, the science of the spread of contagious diseases. Other than a general distrust of science and scientific expertise, there is no compelling religious reason to doubt the scientific establishment’s position on COVID-19, but as of May 2020, two thirds of white American evangelicals surveyed by Christianity Today believed the severity of the novel coronavirus had been exaggerated by the news media, and a further two thirds approved of the Trump administration’s handling of it. One of the reasons cited for not wearing a mask, a measure proven to reduce the spread of COVID-19, is that the advice about masks has changed.

Science gets things wrong often, and communication about the results of scientific research has a lot of room for improvement. Still, self-correcting mechanisms such as peer review, the requirement to disclose conflicts of interests, and transparency about study design mean that results are continually being improved. Results that cannot be replicated by further testing under the same conditions are discarded. Unfortunately, for someone who believes that truth is unchanging, it also means that science is continually proving itself untrustworthy. And, when science strays from accepted wisdom to tell us that sex and sexuality are spectrums, or that being tough on crime worsens crime, or that the most effective solution to drug addiction is to provide free drugs, then science must be dangerously wrong, perhaps even perverse.

If the truth is accessible and uncomplicated, if it does not require training or resources to access, but only a heart that is in the right place, then it follows that gut instincts are valuable in making decisions.

In Frank Peretti’s 2005 novel Monster, an escaped human-chimp hybrid created by an unethical Darwinist geneticist terrorizes an Idaho forest. Peretti meant the novel to be a critique of evolution, saying in an interview at the end of the novel, “One of evolution’s best-kept secrets is that mutations don’t work. I believe that if I can just create a story that somehow addresses that one leg of evolution, I can get people thinking. I can’t make a big scientific argument. I can just tell the story. One of the best ways to really combat the fortress of Darwinism is to allow people to wonder about it, to acquaint them with the controversy so that they know there is one.” In Monster, scientists are motivated primarily by the promise of money and power. The villain reveres Charles Darwin as something like a holy figure: he decorates his cabin with “icons of evolution,” and the code to his laptop is 1859, the publication year of The Origin of Species. A good scientist nervously tells the protagonist that his discoveries challenge scientific orthodoxy, but he doesn’t dare investigate further because his career would be over. Science in this text—and in other white evangelical fiction—is an exercise of institutional power and money, forceful personalities, and inaccessible language; an untrained outsider who can master scientific language can challenge experts and often humble or humiliate them.

White evangelical fiction does not often acknowledge that scientific practice comprises more than words, that it attempts to describe phenomena in the world. The people who have given us new ways of understanding the world are untrustworthy, appealing to arcane practices only an elite few can access. Moreover, we didn’t need new ways of understanding.

CONCLUSIONS: WHAT ALL THIS MEANS

If we recognize that truth looks different to different groups of people, how do we proceed? How do people who disagree on the basic structure of knowledge share common ground, a society, or a country?

First of all, shaming and mocking people for believing as they do hasn’t worked, and won’t work. There is a difference between having different criteria for true information and being willfully ignorant or perverse.

Secondly, we need to improve how academia, scientific authorities, and centre-to-left-wing media outlets publicize and share information. It’s impossible for people who have been branded as intellectual elites to change enough to win over movements that build identities around rejecting them, and it would be wrong to even try. But, at the same time, these movements do have some valid criticisms. Research has an accessibility problem: it costs money to do it and to read the work of those who’ve done it, the results are written in dense language and an inaccessible style, and it still doesn’t always engage well with marginalized communities. Corporate interests do sometimes unduly influence what kind of research receives resources, and how it is publicized. Bias exists. These are issues that have been raised from within research communities, and everyone would benefit from addressing them.

And beleaguered experts do sometimes respond to challenges by becoming arrogant, dismissive, condescending, hostile, or insulting; or by appealing to their authority or to scientific consensus. None of this will persuade someone who has doubts about science itself. Scientists, academics, professors, journalists, editors, and university administrators are human, and subject to frustration. Some of them face systemic oppression and have to defend their own humanity to their audience before establishing their authority and sharing their knowledge. They have every right to express grief, anger, and genuine outrage about this. But the people we speak to are often shielded from the realities of our lives, just as we are often shielded from theirs. I know that I am one person, busy and sleep-deprived, overworked and underfunded, painstakingly cobbling together arguments based on hundreds of hours of research. I don’t think of myself as an elite, but I have the power to clamber up onto the shoulders of giants and speak with authority about my work. For people who are not familiar with academia, my words might come across as lectures from the ivory tower itself, from a system they perceive as oppressive and elitist. In the moment, how much I disagree with this doesn’t matter; my words will be better received if they are as kind and measured as I can make them.

One way of combating polarization is to spend time with people who we disagree with, and to cultivate friendships across the political spectrum. I do not mean that anyone should endure a hostile environment, or to put their physical or mental health in danger. However, where possible, forming relationships is a good way to break out of echo chambers, understand people who think differently, and heal some of the damage that polarization has done to the fabric of civic life. People may not change their minds, but they will have an example of the humanity and goodwill of someone who disagrees.

__

Cat Ashton received a Ph.D. in Humanities from York University in 2018. Her work has appeared in The Journal of Religion and Popular Culture, The Canadian Fantastic in Focus, and Children’s Literature. The insights in this article were first presented in the paper “‘One doesn’t defer to process when dealing with the devil’: Alternative Facts and Evangelical Fiction” for the Alternative Realities: New Challenges for American Literature in the Era of Trump conference at The Clinton Institute for American Studies at University College Dublin, Dublin.

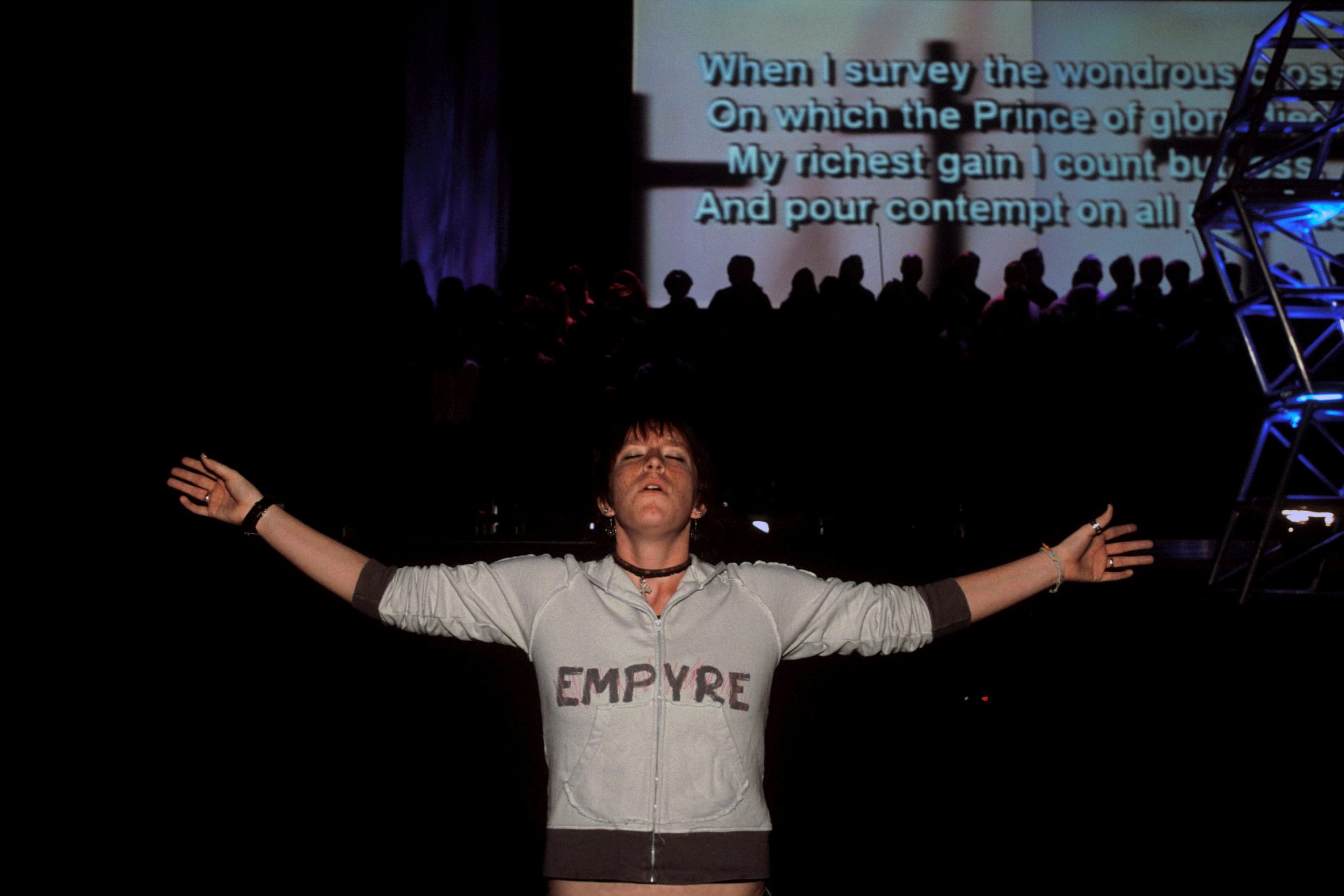

Nina Berman is a documentary photographer, filmmaker, author and educator. Her wide-ranging work looks at American politics, militarism, post violence trauma and resistance. Her photographs and videos have been exhibited at more than 100 venues including the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Museum of Fine Arts Houston, and Dublin Contemporary. She is the author of Purple Hearts – Back from Iraq, portraits and interviews with wounded American veterans, Homeland, an exploration of the militarization of American life post September 11, and most recently, An autobiography of Miss Wish, a story told with a survivor of sexual violence and reported over 25 years. Her work has been recognized with awards in art and journalism from the World Press Photo Foundation, Pictures of the Year International, the Open Society Foundation, and the New York Foundation for the Arts, the Aftermath Project and Hasselblad. She is the 2017 inaugural Susan Tifft fellow at the Center for Documentary studies at Duke University and an associate professor at the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism where she directs the photography program. She lives in her hometown of New York City.

“Secondly, we need to improve how academia, scientific authorities, and centre-to-left-wing media outlets publicize and share information” Thank goodness for Peeps!

To this point specifically, understanding dissemination is key to creating understanding and action. The silo-ing of specialisms tends to work against this, sadly.

We just have to look at the climate change narrative over the years to see the failure of dissemination and story telling in action. If you have to issue multiple Climate Warnings to the world, something is going wrong with the way it’s disseminated (just as one example)…

Agreed wholeheartedly! Thanks very much!

With evangelicals in particular, I think it would be good for people who communicate about climate change to be in contact with organizations such as Young Evangelicals for Climate Action and the Evangelical Environmental Network, who are able to translate and adapt the message for their own communities.