Afrofuturism Answers Back to Afro-pessimism

I remember living in Kenya between 1997 and 2000. At the time, I had just returned to my native country after spending six years of my childhood in France. This was a period in time when the country grappled with the crippling effects of Structural Adjustment policies, usually imposed on “third world countries” by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund.

As part of the conditions for accepting loans, the Kenyan government was forced to retrench many public employees, including teachers. I watched the parents of some of my closest friends lose their jobs and witnessed the economic struggles their families endured as a result. At the time, a stifling sense of despair and hopelessness, a deep pessimism about the nation’s future, permeated the cultural atmosphere of the country. This pessimism about the country’s future was not unique to Kenya. Indeed, despite the high hopes that had energized many newly independent African countries in the 1960s and 1970s, the 1980s were characterized as Africa’s lost decade as the impetus for economic progress and social development turned into socioeconomic decline and social decay.[1]

The term Afro-pessimism gained currency in the 1980s and its prevalence has not abated to this day. Indeed, while the number of low-income African countries with a GNP under $700 per capita was 18 during the 1980s, this number had increased to 27 in 1995[1]. The structural adjustment programs imposed on a number of African countries by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund in the 1990s devastated their economies. In this climate, observers from both inside and outside the continent developed a deep disenchantment about the region’s ability to overcome the challenges that afflicted it, including poverty, youth unemployment and corruption to name a few.

Nonetheless, anxieties, as well as cautious forecasts regarding the futures of many African countries, do not necessarily all fall into the category of Afro-pessimism. Toussaint Nothias identifies five analytical components of afro-pessimist logic:

essentialization

racialization

selectivity

ethnocentric ranking

prediction [2]

Afro-pessimists typically offer simplistic generalizations about the continent that ignore differences among countries. They divide and homogenize the continent along eurocentric racial lines, problematically differentiating black sub-Saharan and Arab/Muslim North Africa, while choosing to focus selectively on negative stories from the continent. As Jon Soske, an African studies scholar, observes in his research on Afro-pessimism “All evils are derived from something essential to Africa, invariably connected to the presence of tribalism. Africans, it is implied, remain forever cursed by their savage and uncivilized past.”[3]

Films such as Blood Diamond,[4] The Last King of Scotland,[5] or even Hotel Rwanda[6] reinforce some of these afro-pessimist assumptions. Even a popular science fiction film such as District 9[7] (set in South Africa) still portrays some African characters as backward, superstitious cannibals mystified by technology (in this case, alien technology). However, a few other films emerging from the African continent have used afrofuturist aesthetics to counter afro-pessimist assumptions. By pitting local political realities against the conventions of film genres, the films question fixed perspectives on African realities.

Afrofuturism questions and undermines the eurocentric idea of progress and the universalizing values of rationalism, and empiricism—and in the process, it breaks down the perceived opposition between “white science” and “black magic.”[11] As Griffith Rollefson, a musicologist who analyzes the works of afrofuturist musicians, explains it “combats whitewashed visions of tomorrow generated by a global ‘future industry’ that equates blackness with the failure of progress and technological catastrophe [by] undermining the normalized disparity between the black body and the cybernetic technological future.”[11] Afrofuturists don’t just place black bodies into previously whitewashed futuristic and technology-enhanced spaces. They question the very idea of progress, including the cultural locations associated with such notions.

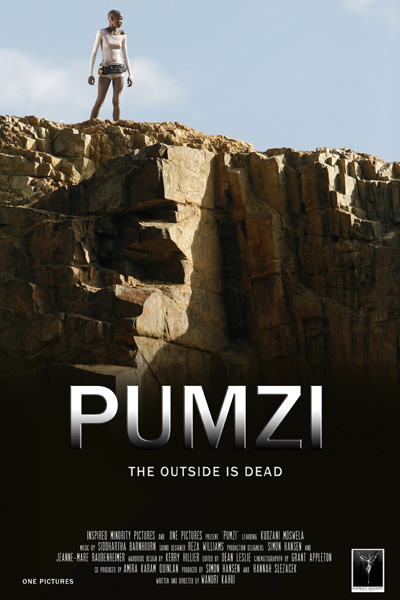

Films, and more broadly stories, do not only shape our perception of the world but also help establish practices used to engage and make sense of the realities that surround us. In the case of science fiction films, at their best, by focusing on imagined possible futures, such works can often compel us to re-examine familiar “common sense” concepts by inviting audiences to imagine alternative ways of engaging the world. In other words, it is by enabling viewers to examine familiar traditions and worldviews from different unfamiliar perspectives and settings that some works of science fiction seek to critique the present while also expanding our vision of what is possible. Kenyan director Wanuri Kahiu’s film, Pumzi,[8] set in a dystopic future, questions the supposed predetermined unchanging hopelessness of present African realities through dystopian politics. Artistic conventions made popular through afrofuturist art are the tools Kahiu uses to critique the present status quo and to imagine alternative futures. Her afrofuturist film places African bodies in futuristic landscapes in an attempt to reveal an essentializing Afro-pessimism that sees African countries as existing outside of time, “progress,” and modernity.

The term Afrofuturism was originally coined by Marc Dary in a collection of interviews entitled Black to the Future, Interviews with Samuel R. Delany, Greg Tate and Tricia Rose.[9] Afrofuturism was depicted as a criticism of US-American science fiction works that tended to depict colour-blind futures in which racial conflicts were nothing more than past insanities that had resolved themselves over time. Science fiction often imagines a world in which racial hierarchies are a thing of the past and where difference is mostly marked through encounters with alien species.[10] Marc Bould, a scholar who has written extensively on Afrofuturism and science fiction, argues that:

The problem with this gesture […] is that rather than putting aside trivial and earthly things, it validates and normalizes very specific ideological and material perspectives, enabling discussions of race and prejudice on a level of abstraction while stifling a more important discussion about real, material conditions, both historical and contemporary [… science fiction] avoids confronting the structures of racism and its own complicity in them.[10]

Afrofuturism questions and undermines the eurocentric idea of progress and the universalizing values of rationalism, and empiricism—and in the process, it breaks down the perceived opposition between “white science” and “black magic.”[11] As Griffith Rollefson, a musicologist who analyzes the works of afrofuturist musicians, explains it “combats whitewashed visions of tomorrow generated by a global ‘future industry’ that equates blackness with the failure of progress and technological catastrophe [by] undermining the normalized disparity between the black body and the cybernetic technological future.”[11] Afrofuturists don’t just place black bodies into previously whitewashed futuristic and technology-enhanced spaces. They question the very idea of progress, including the cultural locations associated with such notions.

Pumzi, set in an East African dystopian world ravaged by war and climate change, also speaks to the large scale economic devastation experienced by many Kenyan citizens in the aftermath of structural adjustment programs. There is an obvious connection between economic and environmental devastation, particularly in Kenya where the people who are the most affected by industrial waste, water pollution, deforestation, desertification and drought are for the most part, poor. In a country suffering from 67% youth unemployment, where many of those youth reside in urban slums, afrofuturist films like Pumzi challenge economic and environmental realities in the present. According to the Kenya Population and Housing Census taken in 1999, young people make up about 60% of Nairobi’s slum population [12]. These youth reside in desolate environments characterized by a lack of available water, proper sewage facilities or garbage disposal services [13]. Many of these slums are also officially designated as the city’s dumping site. By engaging utopian and dystopian politics, Kahiu questions the ways in which these present realities are partially programmed through fatalist projections about the future.

Pumzi begins 35 years after World War 3, also known as the “water war.” In this post-apocalyptic future, the devastating effects of climate change have severely limited the availability of water and life in general. Set in the aftermath of a global war over water resources, the film depicts the lives of a surviving community somewhere in the East African region. Locked away from the inhospitable outside world, the survivors live in a self-contained and self-sustaining high tech underground city protected from the harsh environment above. Members of this surviving community are not allowed to dream and therefore have to medicate themselves with “dream suppressant” pills. The dream suppressant pills prevent them from imagining alternative futures, henceforth condemning them to live eternally in a dystopian present. In Kahiu’s film, the enclosed nature of this post-apocalyptic community, their seclusion from the outside world, also speaks to their inability to think or imagine an existence outside their immediate material realities.

The main protagonist of the film is a young botanist named Asha, who discovers a fertile soil sample from the outside world and sacrifices her own life in an attempt to prove that the exterior environment may still be inhabitable. The film places an emphasis on the importance of visionary dreams. It celebrates the capacity of marginalized people who believe in and work toward the possibility of alternative futures that set themselves against the accepted contemporary dogmas. Thus, despite the dream suppressant pills that she is required to take, Asha experiences a recurring dream depicting a flourishing tree in the outside world. Kodwo Eshun suggests that while critics of colonialism such as Frantz Fanon (the influential anti-colonial activist and critic), “revolted against a power structure that relied on control and representation of the historical archive. Today, the situation is reversed. The powerful employ futurists and draw power from the futures they endorse, thereby condemning the disempowered to live in the past.”[14] Indeed, as the curator of a post-apocalyptic botanical museum designed to conserve the memory of the planet’s former biodiversity, Asha is quickly reprimanded when she steps outside her socially assigned role. As she attempts to persuade her community leaders that the outside world might be getting more hospitable, she is quickly reminded that she is not qualified to make such a diagnosis. She is advised to forward her soil sample to more capable scientists. Asha is denied the social authority that would make her futurist projections credible.

Nonetheless, her role as a museum curator enables her to perceive an alternate way of living and being that is invisible to the rest of her community. The natural museum that Asha curates holds skeletons of animals that are (presumably) now extinct, as well as preserved plant seeds. These artifacts are all meant to document a vibrant past that is now dead. It is by mixing one of the preserved seeds with a soil sample from the present world—in other words, by changing the meaning of the preserved seed from its representation of a lost past (and present dystopia) and transforming it into an active agent of social transformation—that she is able to question the prevailing worldview that defines the world in which she lives. The seed that Aasha mixes with the fertile soil is called a maitu (mother) seed. The construction of the Gĩkũyũ word maitu is briefly illustrated in the film as maa (truth) and itu (ours); thus Maitu, according to the film, also translates into “our truth,” in addition to designating one’s mother. As the element that will give birth to a new future, the seed is defined through the structure of the Gĩkũyũ language, thus offering an afrocentric sense of futurity. Asha’s quest to transform contemporary socio-economic and environmental predicaments, however, comes at the cost of tremendous sacrifices. In the film, Asha not only sacrifices her labour—symbolized by the sweat collected from her body, which she uses to nourish the plant—but also gives her own life. The plant subsequently develops into a magnificent tree and spurs the rebirth of vegetation in this desolate environment.

Kahiu’s film features a strong woman as its lead character. Pumzi adopts an ecofeminist critical position linking ecological concerns to women’s rights. As film critic Sophie Mayer has noted, “Pumzi shows its protagonist literally reclaiming a girlhood lost to waterlessness. In 2010, the World Health Organization and JMP estimated that more than 152 million hours of women and girls’ time is consumed annually collecting water for domestic use. Lack of access to water for cooking, cleaning and personal sanitary use affects women and girls disproportionately.” [15] The description of the “mother seed” frames ecological issues from a women’s rights perspective. If environmental devastation disproportionately affects women in places like Kenya, then they are presented as being the vanguards of social change in Pumzi. In its embrace of afrofuturist themes, Kahiu’s films foregrounds an eco-feminist politics of gender and political power. Indeed, in a global context where the language and cultural logic of patriarchy are often used to justify environmental devastation and social inequities (as exemplified by the ways in which environmentally conscious behavior is sometimes construed to be emasculating by some men), Kahiu’s film emphasizes how feminist perspectives must play an indispensable role in our ability to envision a better and more equitable future.[16]

___

Note

A modified and longer version of this article was originally first published in the Journal of the African Literature Association.

Endnotes

[1] Hyden, G (1996). African Studies in the Mid-1990s: Between Afro-Pessimism and Amero-Skepticism. African Studies Review 39.2.

[2] Nothias, T. (2012). Afro-pessimism in the French and British Press Coverage of the 2010 World Cup in South Africa.”African Studies Bulletin 74 (n.d.): 54-62. 2012.

[3] Soske, J (2004). The Dissimulation of Race: Afro-Pessimism and the Problem of Development. Qui Parle 14.2, JSTOR.

[4] Zwick, E, dir (2006). Blood Diamond. Warner Bros. Pictures.

[5] Macdonald, Kevin, dir. (2006). The Last King of Scotland. Fox Searchlight Pictures.

[6] George, T dir. (2004). Hotel Rwanda. Lions Gate Films.

[7] Blomkamp, N dir. (2009). District 9. Sony Pictures Releasing.

[8] Kahiu, W, dir. (2009). Pumzi. Inspired Minority Pictures.

[9] Dery, M, Delaney R. S., Tate, G, and Rose, T (1994). Black to the Future, Interviews with Samuel R. Delany, Greg Tate and Tricia Rose. Ed. Mark Dery. Flame Wars: The Discourse of Cyberculture. Durham, NC: Duke UP.

[10] Bould M (2007). The Ships Landed Long Ago: Afrofuturism and Black SF.” Science Fiction Studies 34.2, JSTOR.

[11] Rollefson, G (2008). The Robot Voodoo Power Thesis: Afrofuturism and Anti-Anti-Essentialism from Sun Ra to Kool Keith. Black Music Research Journal 28.1.

[12]Achola, Hesbon Otieno. Koch Life: Community Sports in the Slum. Nairobi: Paulines

[13]Erulkar, Annabel, and James K. Matheka. Adolescence in the Kibera Slums of Nairobi, Kenya. Nairobi: Population Council, 2007. Print.

[14] Eshun, K (2003). Further Considerations of Afrofuturism. CR: The New Centennial Review 3.2 .

[15] Mayer, S (2015). Political Animals: The New Feminist Cinema. New York: I. B. Tauris.

[16] Daggett, C (2018). Petro-Masculinity: Fossil Fuels and Authoritarian Desire. Millenium: Journal of International Studies 47.1.