"It Is What It Is":

Trauma as Context in Argentina

“We’re here, fighting. It is what it is.”

For 11 months Dr. Vincenzi has been wrestling with COVID-19 in his Intensive Care Unit on the outskirts of Buenos Aires, Argentina. As we exchange messages via WhatsApp, it is clear he is extremely tired. Dr. Vincenzi is used to the uncertainty, the stress, and the responsibility. He is well-accustomed to the fight.

I first met Dr. Vincenzi when I lived in Buenos Aires in 2018 and 2019. I was there to conduct research on trauma care in public hospitals. I arrived 2 years before the COVID pandemic—before the March in which we all took notice of our inhaling and exhaling, before oxygen saturation rates were discussed on prime time TV, before ventilators became a matter of global concern.

***

It is March 2018. Dr. Vincenzi and I walk through the hospital hallways to the ICU. I ask if there are a lot of trauma patients in the unit right now. “Well, yes. It’s trauma season,” he responds matter-of-factly. It’s summer: warmer weather, more people outside, more cars and motorcycles, more accidents, more traumatic injuries. As a result, the Intensive Care Unit fills up with patients with cerebral edemas, broken legs, fractured arms, collapsed ribcages. We arrive outside the unit, where I see a large clock, neon lighting, and a row of black chairs—the uncomfortable kind meant for waiting long hours in state buildings. There, families wait for what seem like eternities multiplied. Inside the ward, time works the other way around, always in short supply. Entering the unit, I hear the sound of ventilators beeping intermittently as they mechanically force lungs to inhale and exhale.

Dr. Vincenzi works as a unit coordinator at two hospitals to make ends meet, like most medical professionals do in Argentina. He is a renowned neuro-intensivist, a professional who is trained in intensive care medicine and specializes in brain injuries and strokes. He is a tall, broad-shouldered, middle-aged man, with kind eyes and large hands. He’s energetic and pensive, disillusioned and tireless, generous and uncompromising. An Argentine with Italian roots, he quickly takes to me, a researcher raised in Bologna, Italy. “Italians and Argentines, we’re the same, aren’t we!” he jokes, perhaps referring to a shared propensity towards intense gesturing, politics, and tragi-comical dysfunction. There’s a famous saying in Argentina: “An Argentine is an Italian who speaks Spanish, thinks he’s French, and would secretly like to be British.” I am not sure any Argentine would admit to wanting to be British (see the Falklands War or the infamous Argentina-England soccer rivalry). The saying, however, speaks to a long-standing identity crisis—one that emerges from Argentina’s national ideals built around European Whiteness, the erasure of Blackness and Indigeneity, and the confusion of never reaching the promise of “el primer mundo” (the first world). Since its independence from Spain in 1816, the nation has experienced 6 coups d’etat, 6 military dictatorships, 9 debt defaults, triple-digit inflation, and countless instances of currency devaluation. Argentina has lived many trauma seasons.

The intensive care unit is a challenge to the senses: blinding lights, a pungent smell, and constant, intermittent noise. Here you understand what is critical about critical care. Failing physiology is a puzzle to be solved fast. Alongside mechanical ventilation and pharmaceuticals, it is the skills of doctors and nurses that are the unit’s most important tools. Intensivists make decisions, manage uncertainty, and communicate prognoses to families. I see a CT brain scan of a young patient showing bleeding on the edge of his skull, a subdural hematoma, a very serious kind of brain bruise. He was riding his motorcycle without a helmet when he crashed. “I told him this was going to happen,” says his mother next to his bed, as she later shows me a picture of her son. Cheap motorcycles are common, especially in the sprawling peripheries of the city, because cars are expensive. According to the WHO, road traffic-related trauma is responsible for 1.35 million deaths worldwide and 20 to 50 million people sustain non-fatal injuries each year. This epidemiological burden weighs on the lives of individuals and families, but also on healthcare budgets and national economies, especially for so-called low- and middle-income countries like Argentina. But other traumas linger behind these aggregate numbers. A broken skull can engender other fractures: a job lost, a family unsupported, a self often unrecognizable. These breakages occur in broader medical, political, and economic systems that have undergone jolts of their own.

The word trauma comes from the ancient Greek “wound,” but the language of trauma is quite new, dating back to the 1880s and World War I. The “shell shock” of the Great War pushed Sigmund Freud to ask about the lasting wounds of the mind. The category of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is an even more recent formulation, emerging from the activism of returning soldiers from the Vietnam War experiencing psychic distress. Since then, trauma has surpassed its original meaning of physical injury, been integrated into clinical psychology, and entered into conversations about anything from distressing childhood memories to the aftermaths of natural disasters and collective violence.

As a concept, trauma is messy. It is both the event and the reverberations, the injury and the bruise, the experience and the memory. While scientists have found that psychological trauma produces lasting changes in our body’s physiology, physical injuries can do the same to our psyche, as can collective events of shock and ordinary violence.

A broken skull can engender other fractures: a job lost, a family unsupported, a self often unrecognizable. These breakages occur in broader medical, political, and economic systems that have undergone jolts of their own.

Not Scars, But Open Wounds

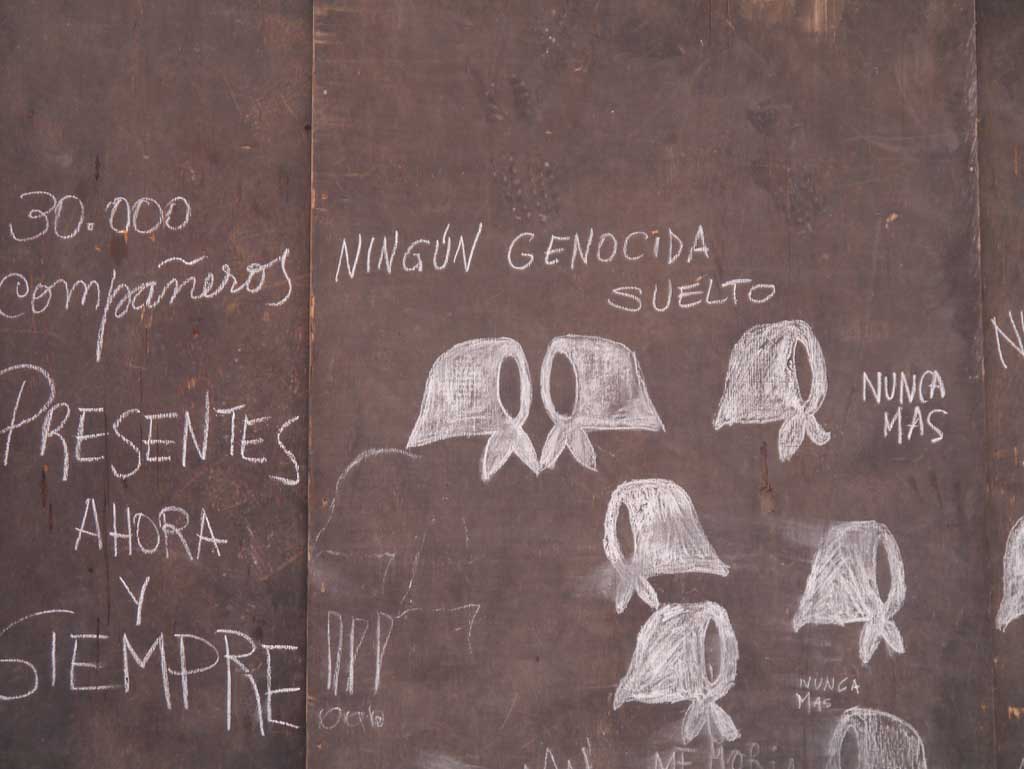

On March 24, 1976, a right-wing military coup overthrew the sitting Argentine president. Congress was dismantled, all radio and television was interrupted, and the junta’s “Process of National Reorganization” (El Proceso de Reorganización Nacional) was enforced through martial law. During this time, approximately 30,000 people went disappeared – desaparecidos – under the dictatorship. Clandestine detention centers were located within city neighborhoods, forming part of what Argentine psychologist Hugo Vezzetti has called the “geography of terror.”

Now in his seventies, Dr. Correa remembers when things at the hospital changed. At the time of the coup, Dr. Correa was a young doctor. He and his colleagues were training as intensivists launching an intensive care unit. When false rumors spread that the hospital was providing care to revolutionary dissidents, the trajectory of their careers was interrupted abruptly. SWAT teams stormed the building. Correa and others were questioned by military officers. Some were detained and never seen again. Correa feared repercussions as he tried to resume his work: “It is hard to find a job in another institution after one is left alone, fired, and held prisoner for days, you know?” Soon after the coup, he fled to Spain with his family, where he lived for a decade.

Amidst the terror, however, there was also stubborn resistance. Starting in 1977, each Thursday a group of mothers made silent rounds in Plaza de Mayo, Buenos Aires’ central square, demanding information about their vanished children. The regime called them crazy. These Madres nevertheless marched with white handkerchiefs around their heads, with pictures of their children in their hands. National reckoning would come much later, but their campaign of silent and steady resistance brought worldwide attention to Argentina and the regime’s human rights abuses.

Today, these wounds are vivid and their scars visible. In efforts to heal and to remember, Argentina is in ever-present tension with its haunting past. Every March 24th, streets fill with crowds holding black and white pictures of those who never returned. The Madres de Plaza de Mayo still gather on Thursdays, and form part of the political and cultural landscape of the country. The association HIJOS (Hijos y Hijas por la Identidad y Justicia contra el Olvido y el Silencio, Children for Identity and Justice against Forgetting and Silence) was founded in 1995 by the children of those persecuted during the dictatorship, and is still active. Activists use escraches, the practice of publicly identifying perpetrators of state terrorism in front of their homes, to deprive these individuals of the tranquil anonymity they have enjoyed in their neighborhoods. And the plaques on the pavement of Buenos Aires, commemorating exactly where people were kidnapped and put into unmarked trucks, mark trauma’s ordinariness in urban life. Memory is never straightforward, however, and people adopt various stances on remembering. In public spaces and private conversations, public marches, political discussions, and intimate mourning, the trauma hits differently. And while the human rights’ refrain “nunca más” (never again) is ubiquitous, ghosts turn up daily.

The hospital where Dr. Vincenzi and Dr. Correa work is a site of such remembrance. Eleven healthcare professionals went missing shortly after the raid. They were detained, tortured, and killed on the hospital’s grounds. Years after, their pictures stand at the entrance with the words “el futuro habita en la memoria” (“the future lives in memory”). Several of their family members work in the hospital today, in a short-circuiting of time and memory. In a memorial for the anniversary of the 1976 hospital raid, the daughter of one of the disappeared recites a poem she has written: “I imagine your ideas and your project. Nunca más, pero vos no estás.” (“Never again, but you are not here.”)

A timeline in the hospital’s grandiose entrance shows the hospital’s history, from the early 50’s to 2017. This was the year when construction workers, installing a gas pipe, found the remains of one of the physicians who disappeared in 1976. However, not everyone was haunted by the discovery. Dr. Vincenzi taps his finger on the poster: “And you know what one of our hospital directors said when they found the remains? Todo este fracaso para dos huesitos.” (“All this fuss for a couple of bones”).

Qué va a pasar?

It is September 2018, and another morning at the hospital. Intensive care doctors and residents congregate around computers to check charts and see how patients have fared during the night. During the review of cases, the large TV screen shows C5N, an Argentine news channel. The volume is muted, but the news anchors’ stern faces hover above the headline, “Qué va a pasar con el dolar?,” (“What’s going to happen to the dollar?”). The segment cuts to International Monetary Fund president Christine Lagarde, with her coiffed white hair and tense smile. She is in Buenos Aires for negotiations with Argentine president Mauricio Macri. Inflation is skyrocketing and the peso is quickly losing ground to the US dollar. “What’s going to happen to him?” I ask about one of the younger patients who suffered a traumatic brain injury from a motorcycle crash several days ago. “Well, depends on how he responds to treatment today,” says Daniél, an attending physician. Throughout my research, Daniél’s colleagues gave me similar answers about almost every case. Predicting the future of a critical patient was something that intensivists consistently shied away from. It was easy to see parallels between the uncertain prognosis for intensive care patients on the one hand, and the economic crisis on the other.

During my time in Argentina, “Qué va a pasar?” (“What’s going to happen?”) permeated the walls of the intensive care unit, among patients attached to monitors and feeding tubes, in the work room where doctors debated worst-case scenarios and best possible outcomes, and in the corridors, where hospital employees wondered aloud if their jobs would be spared by the strict public budget cuts. “Qué va a pasar?” was asked by experts and news anchors reporting the dollar/peso exchange rate hitting a new high. Perhaps it was also on Christine Lagarde’s mind when the IMF offered Argentina the largest loan in IMF history in 2018. It was undoubtedly asked by many families struggling to make ends meet during yet another economic crisis. Throughout my time in and out of hospitals, the question “What’s going to happen?” was asked over and over, in tones of apprehension and resignation.

Argentina’s economic trajectory is often described as a parable of decline, from late 19th century riches to 21st century rags. For economists, Argentina is a paradox: how does a country rich in natural resources, land, and workers lose all its wealth? In the early 1900s, Argentina was one of the richest countries in the world by Gross Domestic Product standards. In 1913, the country had a GDP comparable to Canada, a large immigrant labor force from Europe, and an abundance of farmland and cattle. By the end of the century, Argentina had defaulted on its debt 6 times, taken on large International Monetary Fund loans, and in 2001 declared the largest debt default in the history of the world, all the while enduring cycles of growth and recession. These cycles have become both chronic and familiar to the Argentine people, like being on a forced rollercoaster ride that never lets people off.

To live in Argentina is to be accustomed to incredulity. “No lo puedo creer!” (“I can’t believe it!”) was often the response of hospital staff when the CT scan machine broke down for the nth time, when the printer for patient charts ran out of ink, or when someone was fired after decades of service. All is “unbelievable” until it happens many times over, becoming, actually, quite believable. When Argentina took on another loan from the International Monetary Fund in 2018, the words deuda (debt) and ajuste (adjustment) evoked traumatic memories of the 2001 corralito, when the government froze all bank accounts to avoid massive withdrawals of cash. In the hospitals, these measures meant deep cuts to Argentina’s free public healthcare. At one hospital, severe budget cuts meant that some days there was no fentanyl or propofol, two sedatives critical in an intensive care unit. And while doctors and nurses long ago perfected the art of making do, the unit’s trauma patients experienced the harsh side effects of the neoliberal prescription. Management of the unforeseen applied equally to acute care and national political economy. During my time in intensive care units and trauma wards, it quickly became clear that economics and medicine remained imperfect attempts at such calculations. Predictive models fail as often as they succeed, for doctors and economic analysts alike.

It was easy to see parallels between the uncertain prognosis for intensive care patients on the one hand, and the economic crisis on the other.

With an economy still reeling from the monetary crisis, and hospitals at capacity, COVID-19 is testing Argentina yet again. Buenos Aires experienced one of the longest continuous lockdowns in the world—200 days—and has braced itself for yet another, different trauma season.

En la Cancha

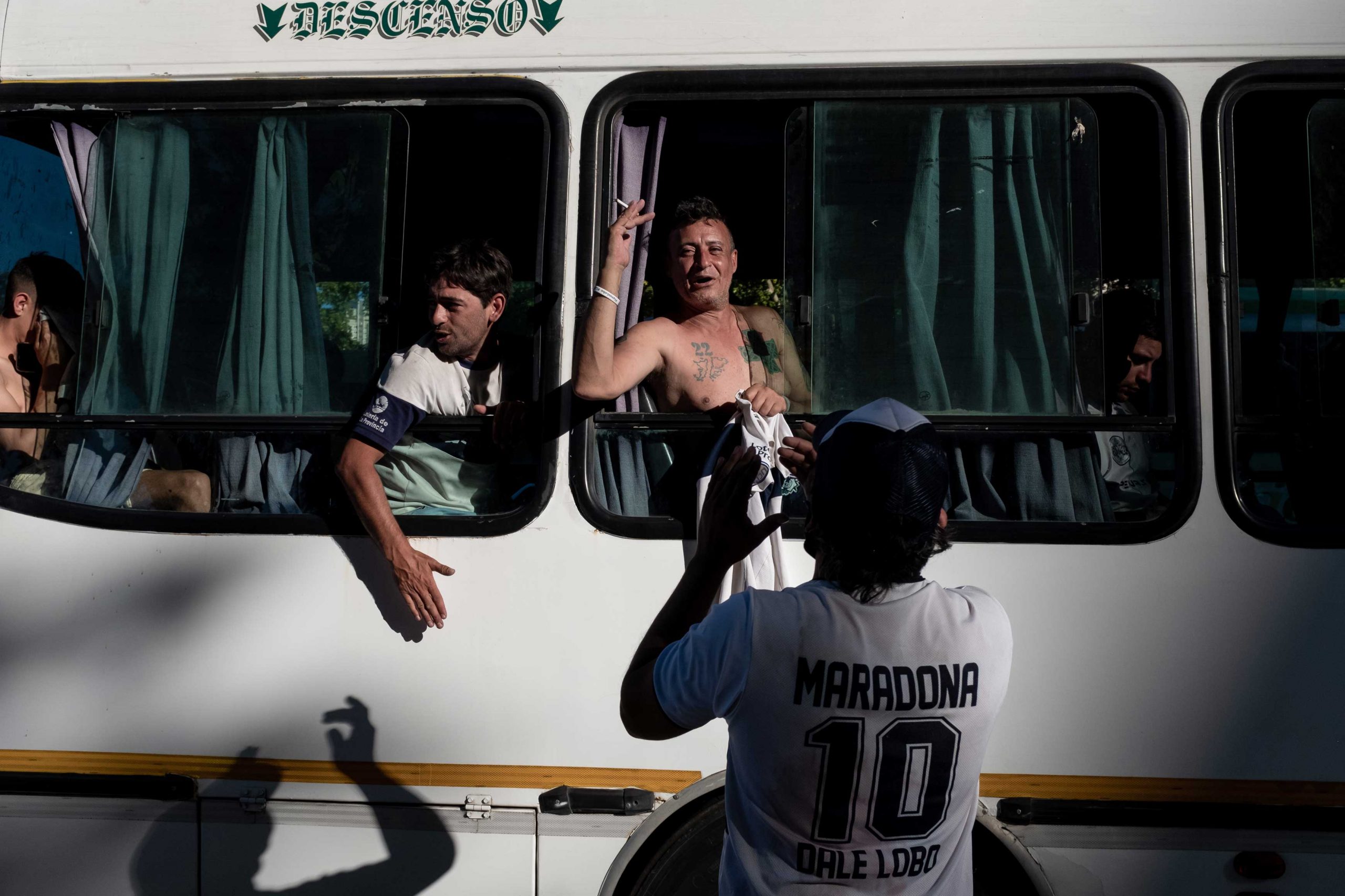

“WITHOUT GOD” (SIN DÍOS) was the headline on November 25th, 2020. Soccer legend Diego Maradona had just died of a heart attack at the age of 60. Known as “El Pibe de Oro” (“The Golden Kid”) and “La Mano de Díos” (“the Hand of God”) because of an infamous goal scored with his hand, Maradona was seen as one with the “pueblo”—his godlike talent tempered by extreme human flaws. Defying COVID social distancing recommendations, crowds filled the streets of Buenos Aires to grieve a soccer player who represented much more than athletic excellence. During three days of national mourning, his body lay in state at the Casa Rosada, Argentina’s presidential house.

Dr. Vincenzi is a big fan of the Football Club Boca Juniors, where Maradona got his big break. Minutes after the announcement of his passing, the ICU’s WhatsApp chat filled with messages of grief, jokes about Maradona’s notorious drug use, and speculation. The infectious disease specialist, Dr. Gutierrez, chimed in, “New question to add to the COVID screening questionnaire: did you attend Maradona’s wake?” It was not the first time that intensive care and intense football drama had overlapped in my research. Along with medical staff, I had followed Argentina’s disappointing performance in the 2018 World Cup directly from the break room. And later, in an interview, a doctor used football metaphors to explain her work in critical care: “It’s like being en la cancha (on the field),” she said. “It’s about being practical because you are going live.” Playing live and fighting for a slim win against the odds, in the most important game ever, is the essence of critical care.

“It is what is” or On Argentina’s Lessons

On a spring day in the middle of my research year, I walk home with Gina, an ICU doctor and friend. Gina has been working at the hospital for decades. She talks about the problems with the hospital, with politics, with Argentina. She is tired after another day of finding beds, finding patients, finding resources, finding strength to envision a different hospital and a different country. Frustrated by cuts and hospital management, she sighs, “They have turned us into this, human beings without a project.”

We reach her house as trees are starting to bloom and daylight stretches into evening. Her backyard is green and lush, a world apart from the hospital’s hallways. We walk towards a big avocado tree, its bounty plentiful each year. She prepares a bag of ripe avocados for me, generous as always. “See, you cannot plan a future here in Argentina. But you either surrender at the first hurdle or you get angry.”

Despite the tenacity of Argentine citizens like Gina, stereotypes about Argentina and its unsolvable puzzles are widespread. Stories about the country often have titles like “The Tragedy of Argentina: a Century of Decline” and “Tango Tantrum.” But the jolts have led to much more than collective trauma, and seeing everything through only that lens would be misleading. These repeated social, political, and economic blows have allowed for required dissent, social solidarity, and “horizontalism,” an emergence of radical movements in the aftermath of the 2001 crisis. Mutual aid, neighborhood assemblies, and worker takeovers of factories are a few examples of what these networks of horizontal power have achieved.

“See, you cannot plan a future here in Argentina. But you either surrender at the first hurdle or you get angry.”

Other forms of collective organizing have spread from Argentina to the rest of Latin America. Since 2015, the grassroots Ni Una Menos movement (Not One Woman Less) has called attention to the staggering numbers of femicides in the country. In 2018 and 2019, the reignited debate on abortion, still illegal in Argentina at the time, spurred public marches and congressional hearings, and brought public attention to deaths due to clandestine abortions. In November 2020, President Alberto Fernandez proposed that Congress legalize abortion. Activists leading the campaign since 2005 were rewarded on December 30th when it passed the Senate vote, making abortion legal in the largest country in Latin America.

In the era of COVID, Dr. Vincenzi and his team, like all healthcare professionals around the world, have had to learn about a new pathogen, adapt their ICU to new protocols, put their own lives at stake like never before, and mourn the loss of many colleagues. On ventilators next to trauma patients are COVID-19 patients struggling to breathe. Last month, after months of putting their own lives at risk, Dr. Vincenzi and his colleagues finally received the Sputnik vaccine.

Yet all these challenges, while new, are not unprecedented for healthcare workers in Argentina or the Global South. The ICU has had to make do, improvise, and deal with many layers of the trauma before COVID, and most likely will have to after. In several ways, Argentina has had a much better coordinated pandemic response than the U.S. and its Global North counterparts, despite its underfunded public health system and a perennial financial crisis. Argentines know all too well how to cope with times of turbulence. But they also know that organized solidarity is the only way forward. After all, es lo que hay, it is what it is. While this sounds defeatist, it is a matter of expecting the worst but hoping for, and working towards, better. Argentina teaches us that acknowledging how bad things are can help us imagine how they can be different. From this place, what can we envision and mobilize? What does trauma close off and what does it demand? While examining past hurts can continuously open wounds, it also engenders a need to act collectively in the present. True—it is what it is. But it can be otherwise.

__

Livia Garofalo is a medical and psychological anthropologist currently completing her PhD at Northwestern University, where she is also earning a Master’s in Public Health from the Feinberg School of Medicine. Her research examines the relationship between intensive care, trauma, and economic crisis in public hospitals in Buenos Aires. Livia has received funding support from the National Science Foundation, the Wenner-Gren Foundation, and the U.S. Fulbright Program. She loves trees, puns, and all things visual.

Anita Pouchard Serra French-Argentinian photojournalist and visual storyteller, based in Buenos Aires, I’m working on current societal and personal issues like identity, migration , women’s rights and territory with a transdisciplinary approach. My work received the support of National Geographic Emergency Fund, Pulitzer Center, WE WOMEN, Open Society Foundations and a International Women’s Media Foundation. I’ve worked for The New York Times, TIME, Bloomberg, Washington Post, Le Monde, Amnesty, and exhibited my work in Argentina, France, Uruguay, Mexico, Spain and USA. I’m also a visual storytelling teacher and lecturer.