Protagonist Issue ❶ ↓ Feature

Winning and Losing in Modern China

Editor’s Note: The following story features insights on the Diaosi community in China from Canadian anthropologist Graham Candy and Chinese photojournalist Yuyang Liu. Candy conducted his PhD field research on Chinese online vigilantism and gaming culture in Hangzhou, China. This story is derived from that research. Liu is an award-winning photojournalist who shot this story in his home town of Chengdu, interviewing and photographing a day-in-the-life of three young subjects who self-identify as Diaosi. Their perspectives have been interwoven in this story to illustrate the nuanced differences and similarities in their points of view and provide a more textured picture of the Diaosi community in China.

—

I first met Hu in 2009. A computer programmer by trade, Hu was earning a middle-class salary by Chinese standards. He was single and rented a room in downtown Hangzhou, a major urban city along the coast of China. Altogether he appeared to have a vibrant social and family life, happily living the modern Chinese dream. By late 2012, he had a revelation of a different sort. Hu proudly told me that he had finally figured it out. In a nation of winners, he was a loser.

The Loser Generation

In 2012, a new term bubbled up from the obscure reaches of the Chinese Internet. The term Diaosi (屌丝), which is roughly translated to mean ‘loser’, was originally used as an insult to mock other online users. By 2013, Analysys International, a consultancy, estimated that over 500 million Chinese—more than a quarter of the total population of the country—self-identified as a Diaosi. This throwaway derogatory slang had seemingly hit a deep and collective emotional chord among the wider Chinese population.

Researchers in China have tried to make sense of this social phenomenon. A report from Beijing University provides a basic archetype: Diaosi make 3,000 RMB a month (483 USD) on average (therefore on the low end of ‘middle class’ in China), typically live far from home, and work in the agricultural, service, or pharmaceutical sectors. They identify as Diaosi because they feel like they do not make enough to buy an apartment or own a vehicle, and they worry about not being able to support their aging parents. Another report by Analysys International suggests that it is actually IT workers and journalists, many of whom earn enough to own cars and apartments, who most self-define as Diaosi. Online, types give way and Diaosi is an identification made by those who earn comfortably middle-class salaries, have mortgages and university degrees, to others who work long hours in factories for little pay, having almost no disposable income.

Despite the variation, there is consensus on three defining features: they are predominantly men born in the 1980s, the large majority play online games (82.5%), and finally, by self-identifying as Diaosi, it means that they do not see themselves as Gao Fu Shuai (tall, rich, handsome, 高富帅). This seemingly innocuous combination of commonalities—masculinity, technology, and class—has in fact situated these so-called losers as one of the most politically dynamic social forces to have emerged in contemporary China.

Modern China is a product of three decades of rapid economic growth. The emergence of a class of young men identifying as losers is confusing, if not contradictory, considering the fact that these are the same young men who belong to an age cohort associated with prosperity.

They are members of the exclusive “Post-80s” group (80后), representing a generation that has supposedly known only of China’s rise in fame and fortune.

Growing Up as Winners

Many online commentators and journalists in China are baffled by the idea that some 500 million people in China consider themselves losers. Even on the lower end, the salaries of the Diaosi suggest they are middle-class.

Modern China is a product of three decades of rapid economic growth. The emergence of a class of young men identifying as losers is confusing, if not contradictory, considering the fact that these are the same young men who belong to an age cohort associated with prosperity. They are members of the exclusive “Post-80s” group (80后), representing a generation that has supposedly known only of China’s rise in fame and fortune. Or to look at it in another way—it means they were born after Mao Zedong died.

Being born after Mao’s death is to be on the bright side of a seemingly epistemic rupture between communism and capitalism. It means that you grew up in the era of the unflattening of the Communist class system that Mao had so fervently defended. It means that you grew up in the era of economic success initiated by Deng Xiaoping through the dismantling of market control mechanisms in the late 1970s. Walk down a street in any large city in China today, and you may still catch a glimpse of what China looked like—the before and after of glass and concrete skyscrapers replacing stout ceramic-tiled homes; new and old BMWs and Volkswagens congesting city arteries instead of nimble bicycles. Socially, the World Bank has praised China for bringing more than 500 million people out of poverty since the market reforms began. Talk with nearly any young Chinese man born in the 1980s and they will tell you that in contrast to their parents who likely spent their youth on communal farms harvesting produce or making cheap state-owned liquor in Communist factories, they received a world-class education and inherited an economy that had grown by around 10% per year for nearly 35 years, one of the fastest in history. The jobs that the self-defined Diaosi hold today did not even exist a generation ago. Being born in this post-Mao era surely means coming of age at the dawn of Chinese winning.

The Chinese Dream

It is perhaps no surprise that within the age of winning the new Chinese President, Xi Jinping, made the center of his ideological platform the so-called collective achievement of the “Zhong Guo Meng” (Chinese Dream, 中国梦). To fulfill this dream, he asked the young to be “ambitious and reliable” and “optimistic and tenacious when facing adversities.” The role of the government, he said, is for “all levels of Party committees and the government to create favorable conditions for young people’s career development.” The goal was to continue the path of growing success in China: more home ownership, more cars on the road, more university graduates and so on. The platform was a hit.

Not everyone is succeeding equally in China today. Particularly the rural poor. The Chinese government frequently declares that better access to healthcare and education is still required and that far too many people live in rural areas where development has only reached sparingly. Their deep anxiety about the rural poor is palpable; after all it was an army of peasants whom Mao recruited from the countryside that overthrew the last government of China. For the government, these are the ‘losers’ who desperately need political-economic interventions to lift them out of poverty and in line with the Chinese dream. Therefore, it is unfathomable that losers can emerge from the bedrock of Chinese society: the urban rich. The Diaosi interrupts this tidy divide between rural and urban to show that there are multiple ways of ‘winning’ and ‘losing’ in China today.

Editor’s Note: Liu, our photographer, is an award-winning photojournalist who shot this story in his home town of Chengdu, interviewing and photographing a day-in-the-life of three young subjects who self-identify as Diaosi. Their perspectives are represented with a blue background to illustrate the nuanced differences and similarities in their points of view and provide a more textured picture of the Diaosi community in China.

Chuanfeng Liu, 22, is from Shijiazhuang city, Hebei province. He has worked at a loan agency in Chengdu since he graduated from college in 2015. He earns a monthly salary of 3000 RMB, which is barely enough money to pay his rent and meals. In spite of this, Liu is satisfied with his work and life at present: ”Although the company is small currently, it still has room for promotion.” However, he constantly struggles with financial affairs in his simple life.

What’s worse, Liu doesn’t have any intimate friends in Chengdu. He would rather play computer games, or drink a little with colleagues on the weekend, than develop relationships with others. He was particularly fond of tennis in the past, but he doesn’t even know where his nearest tennis court is because of how busy he is with work.

Liu became the top seller at the loan agency for the first time in July, selling a 89,250 RMB loan (14,000 USD). He is looking forward to owning a house himself either in Shijiazhuang or Chengdu in about five years. Becoming a general manager of the company in a district in Sichuan is his greatest wish.

In Liu’s eyes, Diaosi is a group of simple, nice, ordinary people—just like other people—who are doing ordinary things but who are struggling with financial affairs in their lives. To him, earning enough money to cover his own cost of living is winning as a Diaosi: “I can decide whether to go to work or not depending on my will, which means I can be the boss of myself. This is winning as a Diaosi,” said Liu.

Hu, The Loser

Hu helped me understand why being a Diaosi was a predominantly male phenomenon, the role video games played in his life, and eventually, the consequences of identifying as Diaosi for his future. Hu lived in the Wenbo district of Hangzhou, a growing metropolis two hours south of Shanghai, with an urban population of 6.2 million. The Wenbo district, in many ways, captured the experiences of contemporary China in a slice of urban life. The rich lived a stone’s throw away from the poor: long-established residents side-by-side with new migrants from the countryside. Polished imported luxury cars weaved around pushcarts and mopeds. The unequal fulfillment of the Chinese dream was on full display, uncomplicated yet by the more invisible form of losing identified by the Diaosi.

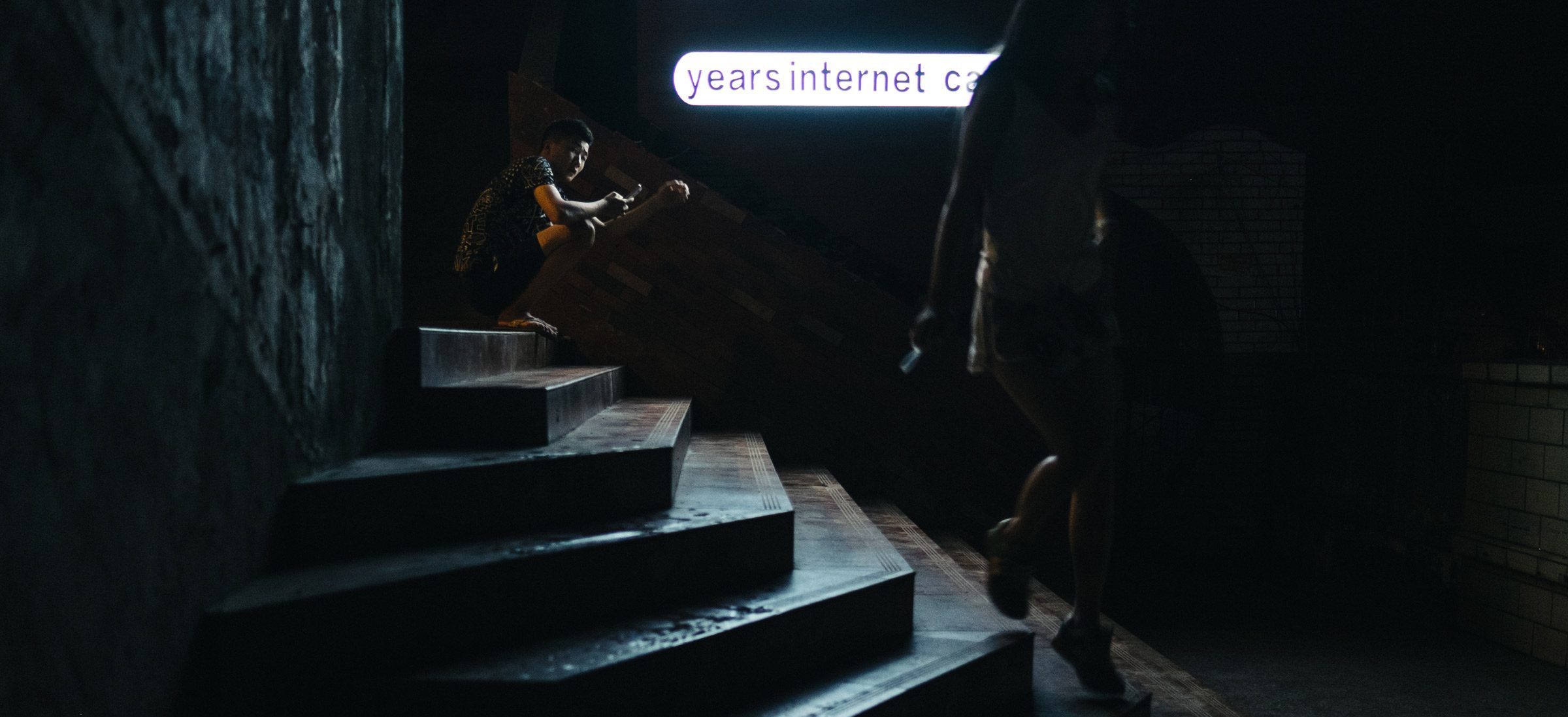

Along one of the major roads ringing the district, on the second floor above a grocery store, there was an Internet café. Internet cafes are known as Wangba (net cafes) in China, and are often filled with dozens, if not hundreds of computers, side by side, set up for online gaming. The air is inevitably choked with cigarette smoke. I met Hu through a game called Counter Strike (CS); a team-based first-person shooter game where players rely on a mix of reaction speeds, strategy and bravado to win. There is no artificial intelligence in CS; you are always playing with and against real people. I was having a particularly good day of shooting. When the match ended, I heard someone yell out my username through the thick smoke, “Who is gcandy?” I walked over to where the voice had come from and introduced myself to Hu. From then on, while I was in China, we played CS each evening. I would talk to Hu in person and over the Internet for the next five years.

Over time, Hu revealed deep anxieties to me about what it was like to be a young man growing up in China and the way in which online video games were an important channel to relieve his deep-seated anxieties. Our conversations helped me understand why people did not, or could not, identify as Gao Fu Shuai, instead gravitating towards Diaosi. A journalist for the People’s Daily recently dismissed this phenomenon as mere self-deprecation, calling for the Diaosi to “give it a rest.”

But what appears as mere self-deprecation can also be interpreted as code for the inexpressible, deep cultural anxieties produced by modern life. One of Hu’s biggest frustrations was his belief that he would never be able to afford an apartment of his own. Hu earned a good salary at around 9,500 RMB (1,500 USD) a month, but it still made buying an apartment anywhere else but in the farthest suburbs an impossibility. Property prices in China have been rising at nearly 10% a year. An average apartment in the city of Hangzhou was listed at over 275,000 USD, over 180 times Hu’s annual income. One may expect that a young man of Hu’s age might be content to rent. In China, however, one of the conditions for marriage is often home ownership, preferably one that is move-in-ready after the big day. Having no apartment of his own was a point of shame for Hu. This was made worse by China’s one-child policy. The cultural preference for boys means that there are far more young men than women. The result is a highly skewed birth ratio of over 120 men for every 100 women. Today, 1 in 4 men will never marry. Hu told me that his only realistic shot was to wait until he was 40 or 50 years old and had accumulated enough money for a small place, if he was lucky, to try his luck again. In the meantime, he often laughingly told me, there was always “singles day” (Guan Gun Jie, 光混节), held on November 11th each year (11/11), a ‘celebration’ for bachelors that involves drinking and purchasing discounted consumer goods online. The consequences of remaining single challenged his filial obligations to his parents and were a great worry for him. As an only child, he was desperately trying to balance saving to buy an apartment with saving to care for his parents when they retire in a few years. All of this, he thought, could be resolved if he just had more Guanxi (social connections, 关系). He, along with millions of other Diaosi like him, believed that in a corrupt and nepotistic China, Guanxi fueled the charmed lives of the Gao Fu Shuai, and left behind are the Diaosi—those without the right social connections for whom it was nearly impossible to succeed.

Losers Go Online

The frustration of the Chinese dream and a future without hope is sometimes too much to bear. For Hu, like hundreds of millions of other Diaosi, online games provide a daily ritual to escape from the realities of modern life. Video games are fun; they are packed with opportunities for achievable accomplishments that make people feel good about themselves. One can say that on a deeper level they fill some of the fundamental gaps that Diaosi like Hu struggle to bridge in their everyday lives.

The relationships that Hu formed online reveal the role of video games for Diaosi in China’s future. Video games foster strong emotional bonds between people that transcend their differences. Hu’s Counter-Strike team brought together a group of people that would never have become socially connected outside of the gaming world due to social taboos and geographical constraints. The five-man team consisted of a forensic accountant working for a large firm in the city, a high school dropout making a living as a carpenter in a nearby city, a university student on a sports scholarship, an 11th grade student performing poorly in school, and Hu, the loser.

Hu told me that it was the sheer experience of testing each one of his teammates’ true personalities that created such deep bonds.

Through playing a game with these people, he experienced tens of thousands of situations where he could judge if a teammate was loyal or not, trustworthy or a liar, a good person, or fundamentally selfish. It is through these gaming practices of intense personal social bonding, that together Hu and his teammates developed their own forms of digital Guanxi that created an online environment that was in contrast to the lack of Guanxi in their everyday lives. His friends were the constant in an otherwise precarious world. His friends were loyal in an otherwise cutthroat society. The relationships they built through CS are sustained to this day. These players were not just his “online friends” said Hu; they were true friends who transcended the gaming world. They regularly lent each other money, helped connect each other with job prospects, and even introduced each other to potential girlfriends. Nearly six years later, and despite the fact that some of them no longer play CS together, Hu told me that he is still in touch with all of them.

Friendship online, however, may not appear to come across as bonding at all. Watch a streaming CS game and you will hear curses and insults volleying back and forth, perhaps more so than the exchange of gunfire. That is because online games are as much a war of words as they are of actions. The veil of online anonymity means that the players will not hesitate to say anything to unnerve their fellow gamers. In response, Hu and his friends learned to utilize the shield of sarcasm. Sarcasm demonstrates to your opponents that you are unshaken by their verbal attacks poking the wounds of your gaming failures. Sarcasm can also be used as ammunition, unleashed against opponents for relentless mocking in the game. The repeated hits to one’s ego and sense of self-worth in the game, Hu said, smiling as he recalled the best insults he had delivered and received, had made him stronger in real life.

Getting up at nine o’clock, going to the net bar after brunch, and staying there until nightfall; this has been Xie’s life for the past two years. Born in 1993, Xie is from Jianyang city, Sichuan province. Xie has lived with his grandmother in Xihe town in Chengdu since he was very young because his parents got divorced when he was 1, and his mother left him to pursue a career. Xie dropped out of school when he was a senior in middle school and got a job.

Two years ago, Xie began to work in a telecommunications company, thanks to an old friend. One month later, he got into an accident. The accident changed his life. “Before the accident I had planned everything out; to become a general manager in the company and save money for business. But I do not know what to do at all after the accident. The only thing I can to do is wait.”

Xie currently has no job but depends on his brothers for the cost of surfing the Internet and meals—nearly 100 RMB (16 USD) a day. He regrets his current situation and feels that he’s getting old: “I have become self-defeated because I have wasted two years.” He said he did not deserve to be called Diaosi, because a Diaosi at least has a job.

But Xie is also conflicted; he doesn’t want to return to his job, ”I feel it does not make sense.” The accident not only changed his plans, but made him clear about something: “After the accident, none of my colleagues in the company came to visit me, even an old friend. I feel heartbroken.” Xie wanted to be a singer—not for fame, but to make a living. But he didn’t stick with it because his family didn’t support him. “It’s the biggest regret of my whole life.” But what delights him is that he might be offered an opportunity to perform as a singer if his brothers open a bar, which they hope to do once they have saved enough money.

Online games are crafting a generation of players who are masters of minutia. Games are high-stress situations where minor details count. It is an environment where the weaponization of information is just as important as sheer skill. Hu was particularly talented at noticing his opponents’ patterns of movement and reducing them to weaknesses in gameplay. In addition, Hu, like many online gamers, developed a skill for scouring for any bits of information that would lead to a strategic advantage in gameplay. It is this last skill in particular that Hu told me he would eventually mobilize in his transition into the world of political play.

Politics of Play

For all of the pleasure of online gameplay, it was not impervious to the frustration and anger experienced in daily life. Long before Diaosi came to stand for anxiety, precarity and hopelessness among young men, these feelings were already palpable with Hu and his online friends. Late at night, after long hours of gaming, team members would find themselves chatting over the voice communication about their real lives, about their dreams and frustrations. For example, one member revealed a run-in with the police that left him bitterly frustrated: he had to pay off the police to avoid jail time after he had been hit in the head from behind and he had punched his assailant in retaliation. Another, the forensic accountant, already had a job lined up at a tier 1 firm but could barely muster any excitement for it. He wanted to be a chef but didn’t dare entertain the idea for fear that he could never support his family. These daily frustrations shared by all the members are characterized most simply by a lack of positive futurity: the sense that the future does not hold the accomplishment of the Chinese dream, but one of struggle and failure to meet even basic cultural expectations.

Things might have never gotten political with people like Hu and other Diaosi if the Chinese state had just decided to leave gamers be. In the first decade of the new millennium, it became apparent that games were growing as a leisure activity faster than any other media form in China. Sensational stories— some real, and some wildly exaggerated— caught the attention of the state: people dying at their computer screens after binge gaming sessions, fires at Internet cafes, and kids failing out of school because of gaming addictions. To the Chinese state, games were sapping the productive energy of an entire generation. There was, and remains today, palpable anxiety that young men, the engine of economic growth, are checking out from the hard work needed to sustain China’s breakneck growth.

Late at night, after long hours of gaming, team members would find themselves chatting over the voice communication about their real lives, about their dreams and frustrations.

Since 2008, the Chinese state has made a series of attempts to reduce gameplay among Diaosi like Hu. They characterized some gamers as having “mental addictions” and recommended shock therapy as a cure. They closed down Internet cafes. They sought to introduce time caps to prevent people from gaming too long. And they delayed the release of new versions of games from abroad to make sure they were “politically appropriate” for China. At one point, one of the most popular games in China, World of Warcraft, one of Hu’s favorite games as well, was delayed for months by internal fighting among different ministries about who had regulatory control over the game. At the same time, the game maker scrambled to produce a censored Chinese version in line with the dictum for all game content: that it is “healthy and harmonious” to Chinese society.

For Diaosi like Hu, these actions were both offensive and ridiculous. He would often quote the powerful scene at the end of a movie released in 2009, parodying the World of Warcraft fiasco. For him, it laid bare what it means to be a gamer and loser in China:

“It’s the feeling of belonging, and four years’ friendship and entrusting (in this virtual community we cannot give up)… just like others who love this game. [We] diligently go to work on a crowded bus, diligently consume all kinds of food with no concern of whatever unknown chemicals (they may contain). We never complain that our wages are low, we never lose our mental balance due to those big townhouses you bought with the money you took from my meagre wage. We mourned and cried for the flood and earthquake; we rejoiced and cheered for the manned space flight and the Olympics. From the bottom of our heart, we never want to lag to any other nations in this world, but in this year, because of you, we can’t even play a game we love whole-heartedly with other gamers all over the world . . . We are so accustomed to silence, but silence doesn’t mean surrender. We can’t stop shouting simply because our voices are low; we can’t do nothing simply because our power is weak. It’s okay to be chided, it’s okay to be misunderstood, it’s okay to be overlooked. But it’s just I no longer want to keep silent.”

For Diaosi like Hu, the rallying cry of his generation came not from the heroes of Chinese history, but from a video game. This speech, which he referred to regularly, became the center of a new kind of politics deeply influenced by both Diaosi cultural frustrations about not being Gao Fu Shuai, as well as the particular skills and relationships he learned and continued to cultivate through online gaming.

Diaosi Do Politics

The Diaosi that does politics in China is likely to have many entry points. For Hu, it was a simple micro-blog post. In 2011, a blog appeared on Weibo (the Chinese equivalent of Twitter). It was called “Brother Hua.” Like many Chinese netizens, Brother Hua decided to take his passion online. He had a penchant for expensive watches: Rolex, Longines, Mont-Blanc, to name a few. Just by looking at a photograph, Hua could name the brand, offer an approximate price, and given enough time, identify the exact model number. His blog was simple in form but extremely powerful in content: he posted single photographs of Chinese public officials taken from official news stories. He then identified exactly what kind of watch the official was wearing and how much it cost. The implications were clear: it was corruption hidden in plain view.

When a photograph of a grinning government official standing beside the wreck of a horrendous bus accident that killed 36 civilians, netizens (Wangmin, 网民) took exception, including many Diaosi like Hu. Netizens first used the photograph to identify the official: a Deputy Safety Investigator named Yang Dacai. Then came the watch on his wrist, its value quickly determined to be 5,700 USD. The Internet erupted: how could a regional government employee afford luxury watches on his middle-class salary? A familiar conversation about government corruption found its voice. Inspired by Brother Hua’s post, Hu and thousands of other gamers took to the forums to vent. The caustic sarcasm honed in years of gaming became the means for veiled political commentary. A characteristic attack on the official, a middle-aged man with a portly figure included: “Well, he certainly hasn’t been starving himself saving up for them.”

Beyond the sarcasm crafted through years of games, Diaosi including Hu utilized their years of digital sleuthing to scour the nooks and crannies of the Internet to uncover other photographs of the official and his watch. They eventually discovered five separate luxury watches worn by the official on different occasions, together worth thousands of US dollars in value. This public “outing” of his multiple luxury watches caused Yang Dacai enough grief and created such a public frenzy that he felt compelled to go online and answer questions from the micro-bloggers themselves, an unheard of action by a mid-level government official. Patiently explaining to a disbelieving online mob, he maintained that he had diligently saved enough to purchase all five of his watches. Unconvinced, Chinese netizens responded by finding still other photos of him wearing two other watches, a bracelet and a pair of sunglasses worth tens of thousands more. The official was sacked, put under internal investigation, and eventually sentenced to 14 years in jail, all because of the diligent weaponization of information by Diaosi. And while Hua’s blog was eventually taken offline, Chinese netizens have taken his technique of ‘watch-watching’ and started looking for other high-profile government officials sporting designer proof of endemic corruption. Recently, the government released guidelines to party members about the sorts of watches they can and cannot wear—showing how Diaosi have held the government accountable on this occasion—through naming, surveilling, and publicizing in the online sphere.

Since 2011, there have been dozens of similar political actions against government corruption. Responding to this new form of citizen power, in 2013 the president discussed the Chinese Dream once again, but this time with a dramatic shift in focus. He pledged the state’s role in stamping out corruption. With a gesture to the original netizen sleuths, his disciplinary watchdog then introduced a government-developed app you can download to follow the new anti-corruption campaign and “blow the whistle” (Wo Yao Ju Bao, 我要举报) on any state official.

Online communities provide Diaosi with the means to forge new social connections and to share anxieties about failures to meet cultural expectations. Unsurprisingly, when the state threatened the world of play, Diaosi responded by mobilizing talents honed in deep gameplay: mocking seemingly untouchable politicians and weaponizing seemingly innocuous information.

The Losers Are Everywhere

The crack that formed with Mao’s death set in motion multiple social, political and economic ruptures that have formed the lived experience of the post-80s generation. They have charged into the 2010s as a generation intoxicated by aspirations for a better future, yet soberly aware of the deep inequalities that run through society. It is at this moment that digital spaces, like chat rooms, forums, and video games have become ubiquitous sites of social connection in contemporary China. Mirroring society at large, these digital spaces too are filled with both winners and losers. For winners like the Gao Fu Shuai, wealth and social connections are amplified. For losers like Hu, it is a humble site for sharing the experience of living a future that never quite materializes as expected, despite the promises.

Online games represent just one technology, yet they play a multi-faceted role in the life of losers: at once an escape, a site to feel good about practicing and honing online skills, a place of deep friendship and familiarity, a world that stays relatively consistent against a precarious and shifting everyday reality. Online communities provide Diaosi with the means to forge new social connections and to share anxieties about failures to meet cultural expectations. Unsurprisingly, when the state threatened the world of play, Diaosi responded by mobilizing talents honed in deep gameplay: mocking seemingly untouchable politicians and weaponizing seemingly innocuous information. Not all gamers are political, but when politics and games intersect, the outcomes are powerful. ●

—

Graham Candy is director of insights and strategy at Diamond Integrated Marketing and a PhD candidate in anthropology at the University of Toronto. gcandy@experiencediamond.com.

Yuyang Liu is an award-winning photojournalist based in China. He is also a contracted photographer for OFPiX Photo, Getty Images China & CFP. yuyangliu.com

_

Winner: Best Original Special Interest Story, Canadian Magazine Awards, 2017

Shortlisted: Best Non-Fiction Story, Stack Magazine Awards, 2016