Thresholds Issue ❷ ↓ Feature

The Rights of the Whanganui River

It was winter, August 10, 2010; a cold, still day. Two days earlier, the Whanganui, a river that runs from the centre of the North Island of New Zealand to the west coast, had been in flood. As we parked outside Pipiriki Marae, a ceremonial centre, mist drifted across the hills behind the little red and white meeting house, its red ensign flag fluttering in the breeze. After the local Maori people formally welcomed us onto the marae, we shared a meal in the dining hall and then joined them inside the meeting house.

Our team, led by Libby Hakaraia and Tainui Stephens, was making a documentary about my great-grandfather James McDonald, a filmmaker and photographer who had travelled down the river in 1923 with a Dominion Museum expedition to record Maori ancestral ways of life. We watched as Libby showed a silent movie and photographs shot by McDonald, including footage of local people working eel weirs from elegant river canoes, displaying their weaving, and playing skipping games in the village.

The local people were fascinated by these images, recognizing places and ancestors, calling out their names and telling stories about them.

The meeting house went quiet when the film showed a tohunga, or priest, performing a divination ritual, chanting and shaking his finger as sticks jerked weirdly across the ground towards some standing wands. Afterwards, Libby, printed some copies for the ancestors’ descendants at the marae.

The next morning, our party—including two cameramen, a sound technician, my husband, Jeremy, and me, with our daughter, Amiria (also an anthropologist), and her son, Tom—boarded a replica ancestral canoe that had been built for the Hollywood movie River Queen. As we paddled down the river, sliding between sheer cliffs green with ferns, the cameramen filmed our progress from a boat.

At one bend on the river, the canoe came to a standstill, caught on an underwater snag. Telling us that the local taniwha (river ancestor) was obstructing our passage, our guide, Ned Tapa, stripped to his wetsuit, dived under the canoe, and set it free. When we arrived at Hiruharama, the next settlement downriver, we landed beside a steep, slippery mud bank and climbed it by jamming our paddles as footholds into its face.

Our team was making a documentary about my great-grandfather, a filmmaker and photographer who had travelled down the river in 1923 with a Dominion Museum expedition to record Maori ancestral ways of life.

That night, Libby showed more film and photographs to the local people, projecting them onto a sheet hung across a corner of the meeting house. The next day, when we visited Ranana Marae, further downriver, an elderly woman told us how her grandmother used to work flax, stripping the fibres used for weaving and dyeing them in living mud, scenes that had been shot by McDonald during the 1923 expedition. As we visited each marae, the river was a powerful presence, linking them together.

In 1994, local tribes argued before the Waitangi Tribunal that the Crown had breached their treaty rights to take care of their ancestral river.

They used McDonald’s films to illustrate the intimacy of their relationship with the Whanganui. Twenty years later, on August 5, 2014, a large crowd including leading Maori chiefs, mayors, ambassadors, and local residents gathered at Ranana Marae, where Whanganui leaders signed a deed of settlement with the New Zealand government, legally recognizing their river as a living being.

It is the first waterway in the world to gain this status. This was a revolutionary step. By recognizing the river, Te Awa Tupua (River with Ancestral Power), as a legal person with its own rights, the Whanganui River was placed in a new relationship with human beings. Key parts of the settlement deed are in Maori. In the opening section, the Whanganui River is described as the source of ora (life, health, and wellbeing), a living whole that runs from the mountains to the sea, made up of many tributaries and bind- ing its people together. This is expressed in a saying often used by Whanganui people, “Ko au te Awa, ko te Awa ko au” (“I am the River, the River is me”).

In the deed of settlement, two people mutually chosen by the Crown and the Whanganui tribes were established as the human face of the river, acting in its name and in its interests and administering Te Korotete (a storage basket for food), a fund of $30 million to support the health and wellbeing of the river. In the settlement, a payment of $80 million was also made to the Whanganui tribes as redress for breaches of their rights in relation to the river under the Treaty of Waitangi.

The treaty, an agreement between the British Crown and the chiefs of many Maori kin groups, was signed in 1840. In the Maori text, which was debated and signed around the country, Queen Victoria agreed to uphold “the full chieftainship of the rangatira [chiefs], the tribes and all the people of New Zealand over their lands, their dwelling- places and all of their prized possessions.” In the English draft, the Queen guaranteed the Maori ancestors the “full, exclusive, undisturbed possession of their Lands and Estates Forests Fisheries and other properties… so long as it is their wish and desire to retain the same in their possession,” including freshwater fisheries and their ancestral rivers, lakes, springs, wetlands, and estuaries.

Since 1975, the Waitangi Tribunal has investigated many complaints by Maori kin groups about breaches of treaty promises by the Crown, including claims relating to the loss and degradation of ancestral waterways holding hearings around the country to address these grievances.

The tribunal has issued reports and made recommendations about particular waterways, generally upholding these complaints. In response to these findings, successive governments have offered apologies to many kin groups around the country and settlements in cash and kind, including co-management arrangements for lakes and rivers.

In the case of the Whanganui River, the tribes had complained that since 1840, without their consent, their customary authority over the river had been taken over by the government. Despite their resistance, eel weirs had been destroyed, gravel removed, customary practices forbidden, fishing rights denied, water use laws imposed, the river polluted, and water diverted for a huge hydroelectric project. As a result, their ancestral river and their way of life has been badly damaged.

In the Whanganui deed of settlement, ancestral Maori conceptions of the relations between the Whanganui river and its people have been recognized, but with the caveat that the agreement does not interfere with existing private property rights in the river. Instead, the use of water is subject to a review process intended to resolve the issues of rights and interests in water, in which the Crown’s position is that “no one, including the Crown, owns water”—although it may be quantified and rights to its use may be licensed, bought, and sold.

In this way, water is set apart from Te Awa Tupua, although, as Whanganui iwi (tribe) members argued before the tribunal, the river is precisely fresh water (wai maori) flowing through time and space, the lifeblood of the land. In explaining their ancestral relationship with the river to the tribunal, the elders recited chants that re-enact the origins of the cosmos. As Viveiros de Castro has argued for Yanonami cosmological accounts, such accounts do not reflect a Maori world view but rather “express the [Maori] world objectively from inside it.”

In these chants, water emerges at the beginnings of the world, when Ranginui, the sky, and Papatuanuku, the earth, were locked together—a single ancestor:

The Earth trembles, the Sky trembles, the Ground trembles, the Source trembles

The numerous trembles, the resounding tremble, the ebbing

The Waters of the Earth, the Waters of the Sky, the Waters of the Ground

The Source of Waters, the ebbing.

When their son Tane (the ancestor of trees and people) forced them apart, allowing light into the world, Earth and Sky wept bitterly for each other. Lakes and rivers, including the Whanganui River, were formed by the teardrops of Rangi, the Sky Father. In Maori cosmology, all the world is a vast kin network where all life forms descend from Rangi and Papa. In this way, the hau, the wind of life that animates the world, intermingles in rivers and people. An attack on the hau of a river is an attack on the life force of its people.

In ancestral times, Whanganui people offered the first catch of the season to a river ancestor to ensure the ora (health, well-being) of the river. If these and other gestures of respect were not made, the hau of the river and its people alike would suffer. This hauhauaitu (harm to the hau) was manifested as illness or ill fortune, a breakdown in the balance of reciprocal exchanges. The life force had been affected, showing signs of collapse and failure.

An elder lamented to the Whanganui Tribunal, “It was with huge sadness that we observed dead tuna [eels] and trout along the banks of our awa tupua [ancestral river]. The only thing that is in a state of growth is the algae and slime. Our river is stagnant and dying. The great river flows from the gathering of mountains to the sea. I am the river, the river is me. If I am the river and the river is me, then emphatically, I am dying.”

Witnesses also described particular taniwha (ancestral guardians with uncanny powers), the places where they live, and their idiosyncratic habits. They discussed the practice of rahui, in which a leader places a stretch of water under a prohibition because someone has drowned there or fish and eels are becoming scarce.

Such associations between people and waterways are deep and intimate. In formal speeches, Maori orators identify themselves by naming their key ancestors, their mountains, and their rivers. After the Land Wars, when many of his territories were confiscated in 1865, Tawhiao, the second Maori king, sang a lament, bidding farewell to his ancestral land as a beloved woman, the Waikato River springing from her breasts:

I look down on the valley of Waikato

As though to hold it in the hollow of my hand…

See how it bursts through

The full bosoms of Maungatautari and Mangakawa

Hills of my inheritance The river of life, each curve

More beautiful than the last

Across the smooth belly of Kirikiriroa

Its gardens bursting with the fullness of good things

Towards the meeting place at

There on the fertile mound I would rest my head And look through the thighs of Taupiri

There at the place of all creation

Let the King come forth

In this cosmology, people, land, waterways, and ancestors are literally bound together—thus the term tangata whenua (land people), the kin group that belongs in a particular place. In this form of order, rivers bind land and people together. It is in this sense that in the tribunal hearings, for instance, the Whanganui River was described as a three-stranded rope binding together the upper, middle, and lower river iwi and assisting the different kin groups to join forces in advancing their claims about the river.

In ancestral times, as elders also told the tribunal, the river was the heartbeat of their people, the pulse of their everyday lives. In each of the villages that lined its banks, there was a marae to receive visitors. In spring people planted gardens, in summer they fished at the mouth of the river, and in autumn they fished for eels, lamprey, and other native fish, gathered berries, and harvested their gardens. They went to the river for healing and rituals of renewal. The rhythm of life was decided by the agricultural cycle and the movement of fish and people up and down the river.

After the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi, however, this living bond between the Maori and their ancestral lands and waterways was assailed as European settlers flooded into the country. European forms of land tenure, based on Cartesian divisions between nature and culture, and modernist ideas about land as private property, were applied to land occupied by the Maori, and Papatuanuku (the Earth Mother) was cut up into blocks for sale.

At the same time, it was assumed that fresh water itself could not be owned. Sir William Blackstone argued in his Commentaries (1765–1769), “Water is a moveable, wandering thing, and must remain common by the law of nature… I can only have a temporary property therein.” Since it was “wild” and “untamed,” fresh water was held to exist in a state of nature, where property rights did not apply.

As European settlement intensified, however, the Crown claimed control of all navigable rivers and lakes in New Zealand on the grounds that this was necessary to protect the national interest in drainage, flood control, and town water supplies. Nevertheless, it did not claim to own the water itself, which was still regarded as part of the commons.

In recent debates over Maori claims to fresh water, the Crown has continued to uphold this doctrine. At the same time, in New Zealand as elsewhere, the idea that fresh water is part of the commons is under siege. From Brazilian rainforests to the Arctic and Antarctic ice caps to “wild” waterways, the last refuges of untouched nature are being redefined as resources for human use.

In this framing, even those who seek to protect these places talk about the services they perform for humanity (in talk of eco-system services, for example), fostering the fantasy (based on ancient myth models that include the Genesis story and the great chain of being) that people are in charge of the planet.

For generations, the Whanganui people have fought against these impositions. By defining their river as Te Awa Tupua, an ancestral being with its own life and rights, and by insisting upon their kinship with it, they have proposed an alternative way of understanding the cosmos. Here, people are linked in complex kin networks with land, waterways, the sea, and their life forms and are locked in intricate symbiotic exchanges with them. These exchanges must be kept in some kind of balance if the hau for land, sea, waterways, and people is to be protected.

Although relatively few marae remain on the banks of Te Awa Tupua, the Whanganui people hold fast to their ancestral river and fight for the rights of future generations to do the same. An elder told the tribunal, “We have been given the task to hold and preserve these things—not for us but for the generations yet to come. Time is like this shadow. It starts to spread out and spread out, and when our shadow is long, we are in line with the old people and the ancestors.”

Just as the local people introduced us (and my great-grandfather and his companions) to the ancestral power of the Whanganui by taking us down the river, paddling through swirling rapids and between fern-laden cliffs, each year a hikoi (pilgrimage) by canoe is conducted from the headwaters of the river to Pipiriki, allowing Whanganui descendants to reconnect with Te Awa Tupua and learn how to take care of its inhabitants: the birds in the bush, the eels and lamprey in the water, and the people. The kin groups want more of their children to grow up on the river, restoring the river and its people to a state of ora.

By defining the Whanganui river as a legal person, the New Zealand government has taken steps to support this aspiration. It will be fascinating to see how this unfolds in practice. The hope is that one day, Whanganui iwi and other New Zealanders may be able to say, “I am the river and the river is me—and I am in a state of ora. We are thriving.” ●

_

Anne Salmond (2014), is a Distinguished Professor of Maori Studies and Anthropology at the University of Auckland, who has won many prizes and international honours for her writings on Maori life. a.salmond@auckland.ac.nz. “Tears of the Rangi: Water, power, and people in New Zealand”(Hau: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 4 (3): 285–309)

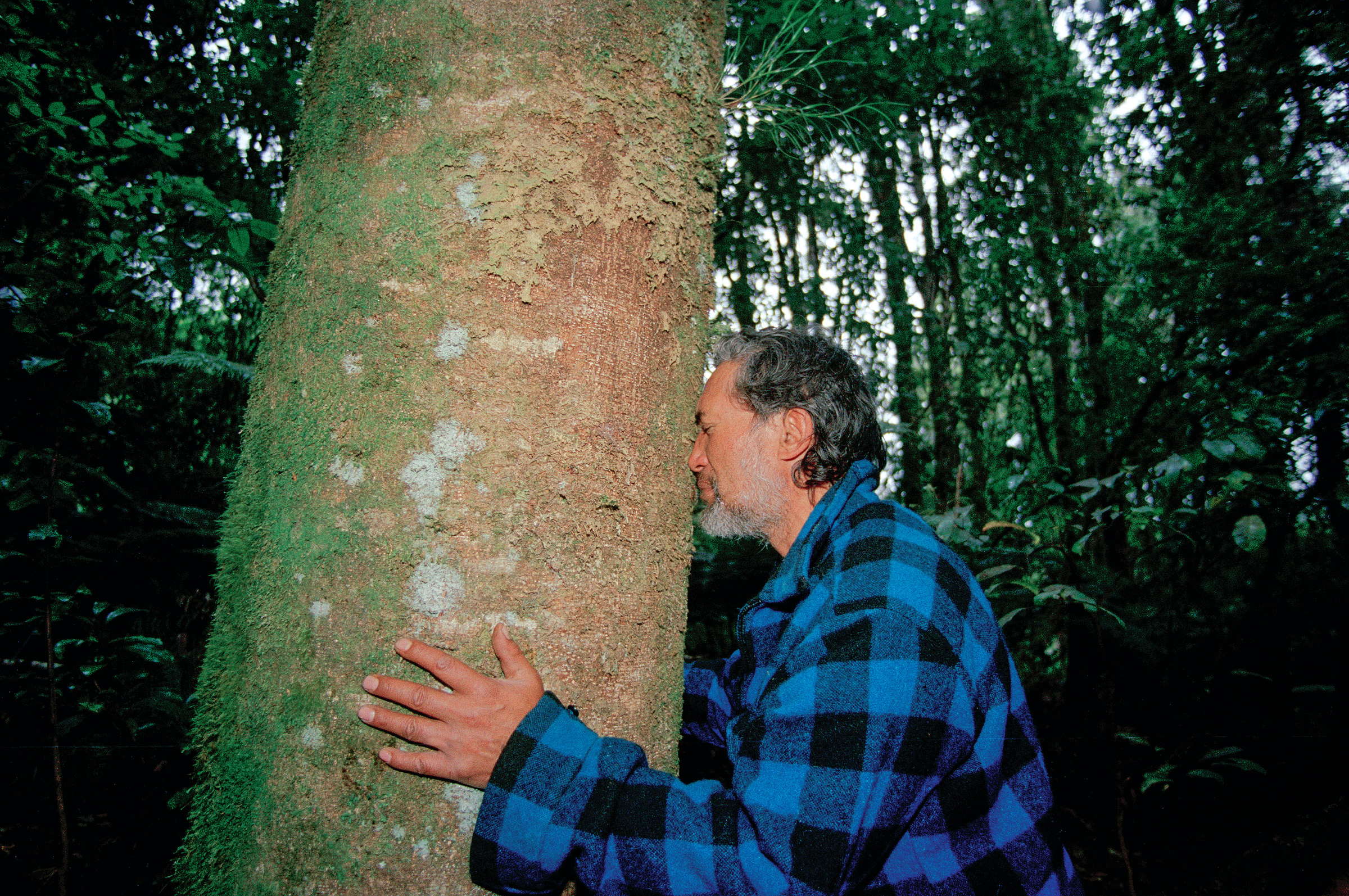

Kerry Brown accompanied Anne Salmon and her team on their trip down the river, taking photos to illustrate their journey.

Martin Toft spent six months meeting and photographing the people who lived along the banks of the Whanganui River. During this time he learned their language well enough to be welcomed onto the marae and explain his purpose. He was adopted into a Maori tribe, Mangapapapa, and was given a native name: Pouma Pokaiwhenu (Pillar of Purity and Food of the Earth.) These photographs tell the story of his encounter with this community.