The Long and the Short of It: Reflecting on narrative, grief and violence in the wake of Baltimore

Baltimore was a place I grew up understanding through my own connections and difficulties. It is my point of departure and something I share with my closest friends, as well as my cultural reference point when I travel elsewhere. It is the city in closest proximity to my own suburban upbringing and later haunts as an adult. It constantly slips into the narrative of my own life, one that will always tie me to a place. In short it has informed my own regional, national and global sense of belonging. I remember numerous occasions in which I would gather with friends, visit ‘Simmy’s’, for wings and mambo sauce (more a DC thing nevertheless food travels) and listen to the latest Baltimore club music in the parking lot; “Peanut Butter Jelly Time” and “Shawty You Phat”. When we could we would venture to ‘the dox’, short for Paradox nightclub on Russell Street, one of the few dance clubs that allowed a younger crowd on Saturday nights.

In late April, I watched from Toronto as Baltimore, a landscape I had weeks prior inhabited, bubbled over from the confines of ‘respectable’ grief and rage. I encountered the first of numerous broadcasts quite off guard. I was sitting in the lobby of a hotel where I often went to write to use the free wifi. In the background the television screen flashed “Violent Riots in Baltimore” as CBC anchors offered up detailed accounts of looting and burning in the streets. How is one supposed to feel when watching their home in conflict? I tense up. I have come to recognize this process as self-preservation. I learned this survival skill young to protect myself from the common-place ‘micro-aggressions’ of racism, hetero-sexism and misogyny. Yet this was not micro-aggression, but something more pervasive. In those first moments of the media portrayals of Baltimore, the latest spectacle of gross violence in America, I felt bottomlessness in my stomach with looming dread of what was to come.

Baltimore’s outcry arose after the funeral of Freddie Gray; another death in a long history of violence caused by conflicts of race and gender, politics and power. Maya Hall, another Baltimore resident and transgender woman experiencing homelessness, lost her life several months prior, also to police violence. Maya’s story is among the many that do not provide the spark for a public outcry. Freddie’s and Maya’s are stories of gross violence that show the problems of racism and state instigated violence. To grieve the life of Freddie Gray means grieving Maya Hall in the same breath, without condition or reservation. Yet how and when these stories enter the global stage remind just how managed and controlled narratives are. Collapsing the nuances of these lives, as the media has, into big narratives of racism and police violence targeting young black men has caused us to lose sight of critical elements of the ways lives are affected by violence and grief. These narratives implicate us in how we mark certain lives deserving over others. We also lose the hearts and minds of so many others that are implicated in this grief. We lose the potency of grief and action.

My own encounter watching these events unfolding were surreal, in part because, having grown up in the neighbouring Howard and Baltimore counties, I knew much of the physical landscape called into question, and had my own friends, memories and associations in Baltimore. However, living abroad made me a spectator, despite my longstanding ties to the area. Since my return to Baltimore, I have had several intimate conversations with friends and family about their encounters as Baltimore residents. On the one hand, I was surprised by how unaffected some were, how distant, as if, like me for a time, they were watching events unfold as a spectator. On the other hand I was drawn to how their lives flew in the face of the depictions of Baltimore proliferating in popular media. During one such conversation, a friend who teaches at one of the local universities commented on how it was as if the campus continued to function like business as usual. Where was this in all of the media depictions?

I wanted to formulate a picture of a public outcry which examined more closely two things. In what ways were depictions of Baltimore polarizing and how did these depictions result in controlling how grief could be felt?

I myself had experienced the aftermath from a TV screen in Toronto. I watched, transfixed, as a CVS that I regularly frequented burned and the North avenue corridor where Artscape, a festival of art and culture which I had attended just the July before, became a zone of violent outrage between residents, youth and the police. In the coming weeks, before my return home, I pored over various articles, media outlets and depictions launched in an almost renewed manner to Baltimore. I wanted to formulate a picture of a public outcry which examined more closely two things. In what ways were depictions of Baltimore polarizing and how did these depictions result in controlling how grief could be felt?

The depictions of Baltimore have been polarized. The stories I read paint an account of Freddie Gray’s memorial and the later physical expressions of grief onto the surrounding neighbourhood by framing residents as ‘thugs’. Representations of criminalization have been rooted in media depictions of rioters that have expanded in recent days to a focus on the hunt for stolen narcotics tied to the riots and statistical data noting an increase in violence. This narrative suggests that the increase in violence is in part due to a gang truce in which the Baltimore police department are targeted. Such claims have since been discredited. Nevertheless, these stories have functioned to deflect from larger local, regional and global concerns. Broader media stories that have sought to connect the death of Gray to a continued siege of violence on black people in the United States have been productive in revealing the dynamics of anti-blackness and racism that is endemic to the United States. The narratives tied to forging community represent this struggle over the story as well. Just this weekend a city worker led clean-up took place at MLK Blvd where a homeless tent community once resided. Such initiatives have worked to ‘beautify’ Baltimore in the wake of Freddie’s death, but at what cost?

Thinking about how we imagine community is to think about how the story we tell of anti-blackness negotiates class and gender. How are we shaping stories of anti-black violence and its grief? How might a public outcry, community clean-ups, marches and protests make visible a grief that had been bottled up for so long? People make stories of their lives. Collective engagements give birth to new relationships in the spaces and communities to which we belong. These relationships forge new stories. These narratives are the objects that shape values and belief systems. In this way, people are invested in these narratives, as they speak to who they believe themselves to be. But these stories are not always true, and they are not true for everyone. That is the trouble with stories we have invested in, and in particular those that include stereotypes of groups of people, or identity more broadly.

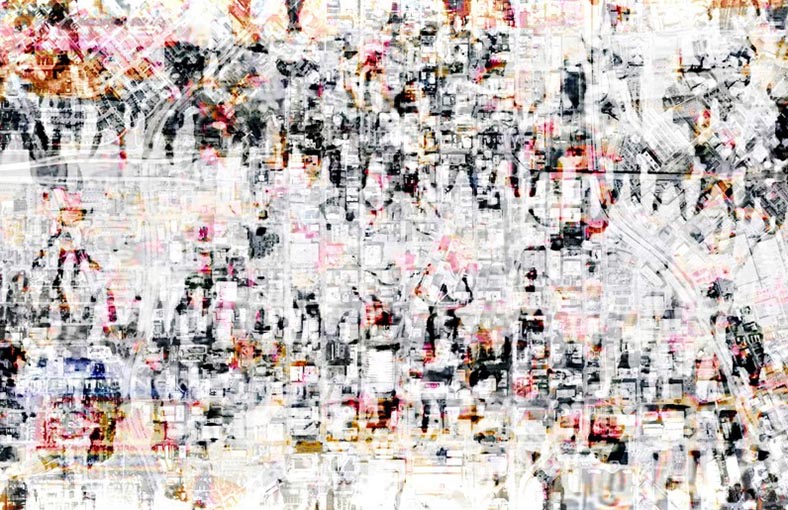

What then does it mean to tell stories of the communities we imagine and a boundless grief experienced? When these narratives are linked to images that we see and consume in public discourse, how do our relationships change? Traveling a block, a neighbourhood, a country lays plain how important stories and images, media, are to us. In traveling, narratives and image converge and diverge. They clash in struggle. Can we envision these relationships to the communities in which we see ourselves a part of as opportunities to imagine different possibilities for black existence, and more broadly, human existence? What then are our vested interests, in the images we see, the stories we tell and the bodies under siege? What do they tell us about ourselves? And where do our vested interests lay claim to a history that we are not prisoners of? One possible answer is imagining a narrative in which black lives matter, but also in which black lives mattering has everything to do with all of us. As in Baltimore as it is in Charleston, how will the story be told?

In the meantime, Baltimore remains a space in flux. The story of Baltimore is about feelings. The images and stories coming out of it are connected to feelings and grief controlled at times for public relations strategy. The groundwork for what happened in Baltimore was set already, like numerous spaces in the world. At some point the tiger wants to get out of the cage. The tiger wants to be free. You can contain, beautify and smooth over grief for so long before it spills over in excess. How will grief be controlled? What will we tell ourselves of the lives we lead? ●

–

Sarah Stefana Smith is a Washington D.C. and Toronto-based artist and scholar, completing her PhD in the department of Social Justice Education at the University of Toronto. Her interests include Black diaspora art and culture, visual studies, affect and queer theory. In 2013 as a recipient of the Bremen International Student Fellowship Program, Sarah guest lectured on photography and slavery at the University of Bremen. A recipient of the Leeway Foundation Art & Change Grant, and later Ontario Arts Council she completed her MFA in Interdisciplinary Art from Goddard College in 2010. Originally from Baltimore, Maryland Sarah has exhibited in galleries and alternative spaces in Atlanta, Philadelphia and Toronto, including the 40th Street Artist residency (Philadelphia) and the High Museum of Art (Atlanta). She is looking forward to being an art teacher at a charter high school in the Fall. Stay in touch with her at www.sarahstefanasmith.com