In the Beginning, there was Sparks

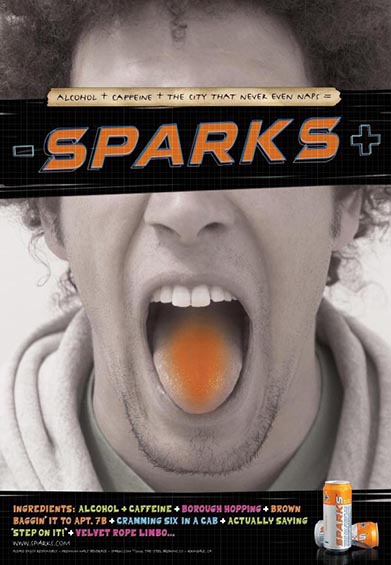

In its original formulation, Sparks was one of the first alcoholic beverages to contain caffeine. Its other original active ingredients included taurine, ginseng, and guarana, the backbone ingredients of traditional energy drinks. It also contained 6% alcohol. Packaged in a can that looked like a AAA battery, its labeling boldly and loudly stated all of its ingredients and its 6% alcoholic content by volume. Its flavor was similar to other energy drinks mixed with malt liquor, having a tart, sugary, synthetic taste. Its color was a vibrant day-glow orange. All of this added up to a drink that caught the attention of twenty-somethings. They were the people in the know; tattoo chic, experimenting, and bringing trends to life, not the people on the cutting edge of what is cool, but not the late comers to the subcultural party. Sparks was a catalyst for exploring a wilder side. It was what you took to a party, a kickball game, a rave or an outdoor concert.

Sparks was bought by Miller Brewing in 2006, but for all its success, Miller’s initial marketing campaigns fell flat. Sales, though strong, remained essentially unchanged from one year to the next. While the success of Sparks was tremendous, they hadn’t a clue about the people drinking it. There was plenty of data about the age group, but when it came to the lives and habits of the consumers, they really didn’t “get” them. Despite all of the traditional marketing data they held in their hands, Sparks was shaping up to be a puzzle they couldn’t solve. And so they reached out to ethnographers to get at the heart of the matter. What was it about this drink that Miller just didn’t quite get? After spending $125 million on the product, Miller was decidedly keen to get to the bottom of this mystery.

Shaping the Campaign

Initially, Miller had relied on a traditional campaign strategy—images of people at fairly tame social gatherings, savoring Sparks the way one might savor a beer after a long day at work, focusing on flavor. They even considered changing the formulation of the drink to offer an array of flavors that weren’t so dramatic, packaging the cans in twelve packs for sharing and easy storage, and mimicking other beverage producers with on-premises promotions that emphasized flavor and direct competition with the Red Bull and vodka crowd. In the end, Miller chose a different route, based on what came out of the fieldwork. The strategy focused on the one thing that made Sparks special; its sheer absurdity and embodiment of sanitized rebellion.

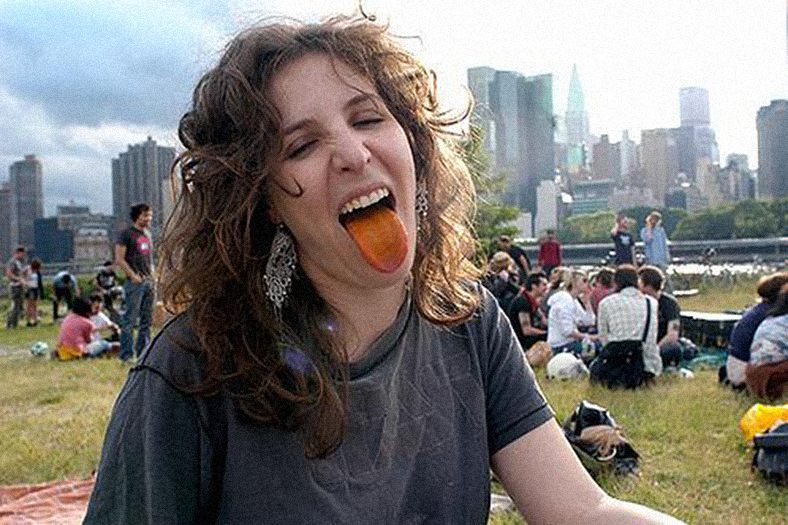

Sparks was defined by its users. They felt a large degree of control over it and a deep appreciation for the fact that its ingredients simply weren’t meant to go together. Sparks represented a categorical frame that defied convention and the campaign we helped them develop reflected that. The focus moved away from traditional advertising and competing directly with the competition. Instead, the strategy was to become a presence at transitory events such as raves, mutant bike rallies, skateboarding competitions, music festivals that weren’t in the mainstream, but not so far outside the norm as to be overlooked. Events were chosen that reflected a sanitized sense of rebellion. Photo-bombing was encouraged and recipes were shared. One Brooklyn kickball team took it upon themselves to use the Sparks can as their mascot, shooting it “doing things” before every game, which led to competition between teams for posting the best shots. One woman and her roommate gave the world their recipe for a Sparks float. While the drink is interesting, having had a couple of Sparks before trying it helps with the flavor.

The other central aspect of the campaign was to focus on small, stop-and-go liquor stores and groceries, rather than worrying about what happened at the bar. Bars are about the projection of sophistication, group affiliation, and building group identity in a closed environment with certain social rules. Sparks was all about the individual drinking it and being part of a group activity defined by being temporary and over the top. The places where Sparks was consumed were about mutability and liminality, which fit right in with the places it was typically bought. Finally, the product itself saw no change. Making it taste “good” defeated the purpose and devalued the drink. It was one thing to introduce Blackberry Sparks, but quite another to mask the strange, chemically flavor notes that made the drink cool. Equally important to keep the unusual flavor, changes to the packaging were made to reflect its utility, giving it greater symbolic credibility and making it something you could show off to your friends and strangers.

All of these elements came together to ignite a simple idea: Sparks isn’t something you drink so much as it was something you used, whether for the obvious physical effects or to set the stage for an evening (or, less often, a day) where abandonment of social norms was the rule. This meant Miller had to embrace greater risk and deviate from its normal operating procedures. They couldn’t stick with a brand image that was intentionally subdued. They could focus on the middle of the bell curve, but had to embrace the people who were setting trends. It was a gamble, but one that paid off. Under the new campaign direction, Sparks saw sales and awareness increase 20% after having been stagnant for well over a year. So how did we get there?

Heading into the Field

In the case of Sparks, we met with our key informants and their friends in their homes and hangouts. This meant going out on the town, so to speak, as they engaged in any number of activities. Inevitably, this led us to bars, parties, etc. Being in the moment, taking advantage of unexpected fieldwork situations to gather information, became the unspoken mantra of the research. One of our key informants had us meet in her Williamsburg apartment the night she was throwing a party. Much to our delight, nearly everyone attending had a couple of cans of Sparks with them, along with a six pack of something else, usually an import. The six packs went in the fridge or on the fire escape, it was a brutally cold winter, so people took advantage of the situation, but the cans of Sparks stayed with the owner. What we discovered was surprisingly simple—one can was used to kick start the evening and the other was downed at about midnight or 1:00 to keep the party going. Functionally, the product was all about what several participants called the “pre-funk”.

But Sparks isn’t as simple as the obvious functional benefits. It’s property that is guarded, like someone’s stash. And more importantly, it’s a symbol that tells everyone the drinker has a license to break the rules and to turn the night into something more than a casual get together. Inevitably, when you’re drinking Sparks, the expectation is that you’ll be out late engaging in the unexpected. In one case it meant heading to a rave in the Bronx, followed by a sunrise trip to Hoboken to find a place that served legendary waffles. In another, it set the stage for semi-nude wrestling on the front lawn in the cold and damp of a Portland winter. The important thing to take away from this is that a pattern of behavior emerged that we wouldn’t have gotten had had we simply conducted an interview. We had to be in the moment.

In one case we found ourselves at the apartment of a 28-year-old male living on the Upper East Side. He had gotten into the mix because he was making under $50,000 a year (the majority of Sparks drinkers were not affluent and so the client had asked that we cap the incomes). However, the participant, Marco, was taking time off from his job as the head of social media for a major clothing brand. At the time he left he was making upwards of $300,000. As it turned out, while he stocked his pantry with high-quality wines and liquor, he was also an avid Sparks fan. Not so much for its energy properties, but because it allowed him to reconnect with what he saw as his rebel past. Marco recounted his early years in New York, struggling to get by and living a romanticized quasi-punk existence. Every Sunday, Marco would spend the day in Brooklyn with his pre-affluence friends building and riding mutant bikes and the searching out the “worst” or “most ridiculous” drink possible. For Marco, and for almost all the Sparks fans we met, Sparks became a something that not only gave them symbolic license to act in ways they normally wouldn’t, but also provided them with a sense of connection to their youth.

Heading Home—Moments of Insight

After leaving the field the hard work begins. Literally hundreds of pieces of information from different field teams have to be synthesized into a meaningful set of patterns, and the final output can be large and daunting. That works well if your goal is academic, but when all is said and done, our clients are looking for direction and specific ideas on which they can act. In the case of Sparks, several key conceptual points bubbled to the surface. The first was to capitalize of the idea of function vs. connoisseurship. Sparks has a fairly clear purpose of establishing a physical state vs. status. Unlike, say Oban (seek it out if you’re unfamiliar), Sparks does not convey taste or knowledge about culinary matters. It does convey knowledge about being part of the inner circle of cool.

Above all else, Sparks functions as a means of kicking off the night and gives the drinker license to behave in unexpected ways. Second, Sparks has an undertone of humor to it. Throughout the research, participants talked about the cartoonishness of the drink – the “absurdity” of the battery-like can, the color, the very idea of combining malt liquor and an energy drink. Sparks was a manifestation of incongruity in beverage form, bricolage in a can. Not surprisingly, urban myths and folklore about Sparks were in ready supply. For example, more than one participant told us, “If you drink more than three you may die”. Another told us that if you leave a glass of it out overnight, it would eat through the bottom, though they had never tried the experiment themselves. One participant firmly believed that if taken to a picnic, Sparks would be the only item ants would avoid. None of it was taken all that seriously, but that simply added to the fun. The brand’s very absurdity was a major strength.

Finally, Sparks tied in with symbols of youth. It signified rebellion and a lack of inhibitions. It also represents a sense of abandon where mortality is challenged. Almost everyone we spoke with commented at some point that they would stop drinking the stuff before they were thirty. As one participant said, “I know this stuff is killing me, but I’m still young, I have time.” Sparks tempts fate, it reifies the drinker’s youth and briefly puts them in opposition to the larger culture without having to commit to a permanent state of rebellion.

All of this led to a number of clear recommendations, some of which flew in the face of what the data and the focus groups said. First, it was extremely important to keep the flavor funky. Tasting strange, like the color of the drink, gave it credibility. Tasting strange solidifies it as a symbol of absurdity, making the drink a publically displayed symbol of their “inner cool.” Second, Miller had to rethink packaging. Like the flavor, the can itself is a symbol drinkers use to let others know that social norms are fluid while drinking it. But this is not a drink you share. You only drink 2-3 in a night, which meant six packs are useless. It’s all about grab and go, not something you stockpile, savor, or sip with friends. That means designing two packs and three packs. Third, the brand had to accept that on-trade is not where success lies, at least not initially. Cans in a bar are unacceptable, unless the product is seen as a throwback drink (i.e. retro beers, etc.). On the surface, Red Bull and vodka might not appear that dissimilar from Sparks, but what they convey in a bar is vastly different. Cans are acceptable in public space when it is truly public. Finally, Miller needed to rethink traditional media. Because of an inherent distrust of advertising, the rise of social media, and word of mouth being the most trustworthy means of communicating “cool”, print, radio, and TV had little relevance. Live events and being in unexpected places, such as sponsoring a last-minute street party or having a presence at a mutant bike rally, adds credibility and cache to the brand. Sparks, unlike the other products in the parent brand’s suite, needed to break away from everything the company was comfortable with. Indeed, it needed to work in opposition to it.

The Sad Demise of Sparks

Unfortunately, for all its success, Spark has faded into the background, the reason being that all the “good stuff” was removed, stripping it of the very things that made it work. In September 2008, the Center for Science in the Public Interest, a Washington D.C.-based watchdog group, sued MillerCoors (Miller Brewing and Coors had merged the year before), claiming that its Sparks alcoholic beverages that include caffeine are a health hazard. Next, Congress began a probe. But the suit never made it to court. Three months later, at the behest of San Francisco and 13 states, distributor MillerCoors buckled and announced it would remove the caffeine and other energy-drink ingredients from its Sparks line of energy drinks, and would change its marketing campaign. With the ingredients gone, Sparks simply didn’t have a campaign or a product that mattered. The drink still exists, but the brand has fallen into the shadows of the broader MillerCoors portfolio as sales have declined over time.

For better or for worse, the work we did increased awareness, market share and sales. Unfortunately, it also helped put the brand squarely in the crosshairs. Had Sparks remained quietly in the background, it might not have garnered the ire of watchdog groups. The drink was representational of the people who drank it: outsiders, rebels, people who are often seen as a threat by the standard order. Sparks, like heavy metal or punk in the 80s, was more than a potential health hazard, it was a threat to the status quo. By bringing it into a more accepted space, it challenged what drinking “should be”. And so, Sparks became a target as it grew in popularity, and ultimately was undone by the very factors which had driven the marketing campaign that had made it so successful. Even so, what the client and our team learned from the research done on this project continues to be used to this day, which, as far as I’m concerned, is the greatest compliment a project can receive. ●

—

Gavin Johnston is an anthropologist and proven research professional with over 14 years of experience integrating and synthesizing consumer and shopper insights for collaborative brand development, marketing and design. www.anthrostrategy.net